The Helper’s Crossroads

This blog was originally posted here.

Institutions that seek to help through the provision of programmes and services, in Ireland and elsewhere, have rightly been criticized for providing supports that are often experienced by those that receive them, as being:

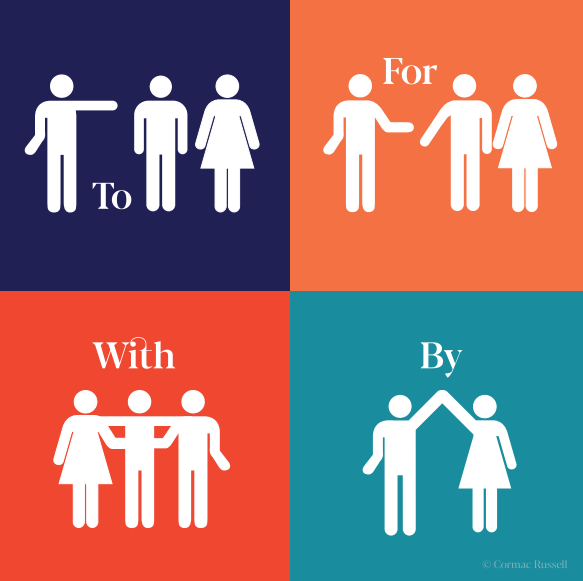

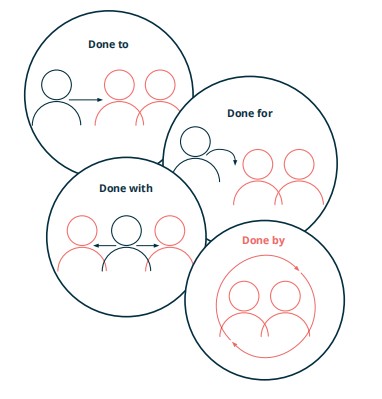

1. Done to citizens: coercive, educative/directive, seeks to fix/cure, or

2. Done for citizens: less coercive; moving towards deeper involvement, but where the professionals nevertheless remain in control.

In recent years there has been a shift in institutional practices and policy discourse in Ireland towards:

3. Doing with citizens: this approach, sometimes referred to as a partnership or co-production approach, aims to transcend “doing to and doing for” as described above, by promoting more equal and reciprocal relationships. As well as promoting co-design, co-decision making, and ongoing co-evaluation, “doing with” approaches, therefore seek to augment co-design of services and programmes and to supersede the doing to and for approaches by promoting genuine processes of co-delivering.

Asset-Based Community Development

Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD) approaches by comparison do not just go beyond top-down “doing to and for”, they also go beyond “done with” approaches. This is because ABCD promotes principles and processes of community driven and citizen-led change. ABCD also asserts that community led change efforts are a necessary precursor to partnership and co-production between institutions and citizens, if the change is to endure and be sustainable.

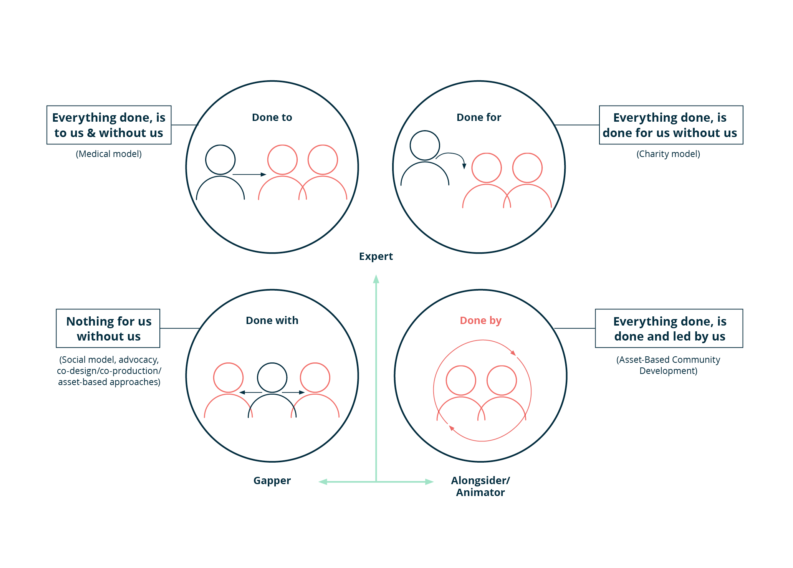

“Doing with”, which is now popularly known in Ireland as co-production, when done well invites citizens into an authentic relationship with professionals and their organizational dynamics, but those relationships typically occur within the limits of the service paradigm. The “By” mode of change in contrast moves beyond the service paradigm, and into citizen space. Citizens space is the domain where citizenships deepens and citizen-led action -ranging from neighbourliness to non-violent protests, and includes volunteering, voting, organ donation and a myriad of other civic acts- occurs. The diagram below represents the four modes of changes with “By” in the foreground and “To” in the background, to highlight the optimal relationship between the modes, from By to With, the For, and To remaining as a last resort.

I have labeled this new topology The Helper’s Crossroads to reorient us towards a different social order, one which involves firstly identifying and productively connecting unconnected local resources by intentionally adopting the following sequence wherever possible:

-

- Starting with what residents (inhabitants) can do themselves as an association of citizens, without any outside help. (Done by)

- Then looking at what they can do with a little outside help. (Done with)

- Finally, once these local assets have been fully connected and mobilized, citizens decide collectively on what they want outside actors to do for them. (Done for).

The order is critical. When we start with the third step, Done For, or worse Done To, as often is the case with traditional helping endeavours within institutions, we preclude citizen power.

In effect, the recommended sequence is a means of operationalising the principle of subsidiarity, whereby an outside actor should perform only those functions which cannot be performed at the local level. Put more plainly, a professional following the principle of subsidiarity would not do for citizens what they can do for themselves or through collective citizen effort.

The Helper’s Crossroads 2.0, illustrated below further shows how the four domains can co-exist and enhance each other when the process is authentically citizen-led, not expert driven. That schematic proposes that professionals operating within the ‘done with’ space are occupying a gap between institutional/contractual worlds and civic non-contractual worlds. To do so competently requires that they function bi-culturally and bi-lingually across those spaces. It also means that they must be willing to challenge institutional and organisational overreach that comes in the shape of the professional impulse to do “to or for” people that which they can do themselves within their natural social context using local assets – which would constitute a step back from citizen space.

The 2.0 version of The Helper’s Crossroads also makes explicit another role that professionals working in citizen space can usefully take on, the role of the ‘Alongsider’. The Alongsider is not an insider, nor a complete outsider; rather, “Alongsiders” walk along with communities, in a non-prescriptive and non-directional ways. The key distinction here is that they are not acting as would traditional outside actors on behalf of an institution, by providing a service to or for people, neither are they co-producing a service with people. They are facilitating space for citizens to join together to co-create what matters to them as communities, that space is largely outside of services and contracts. It is within such space, that citizens can join together to co-create a wide array of experiences including love, laughter, friendship, kinship, mutuality and power, all of which are critical determinants of well-being.

Indeed sometimes the process of creating space may mean getting out of the way or removing bureaucratic barriers; or the reverse, where what is required are strong governmental regulations to curb predatory market forces. With regards to the wider political sphere, this new topology of the four modes of change exposes how misguided and misguiding the ‘big government’ versus ‘small government’ debate really is. The subsidiarity principle is not a matter of keeping government small so that commerce and communities can grow bigger, it is rather a more nuanced deliberation about proportionality, since there are occasions when communities will need governments to be big enough to create a dome of protection around them. And yet other occasions when communities require governments to be small enough to ensure they do not solve problems that are best solved in the commons.

Stronger citizens living in flourishing communities can bring great influence to co-production (Done With) discussions and also take on authorizing roles when professionals are required to legitimately do things to or for communities. Such shifts in part occur at a conceptual level, but real impact on the social order can only occur when practice changes in everyday contexts as well as at the organizational level. The challenge then remains to translate the above conceptual argument into practical application, by considering how ABCD can act as a buttress to authentic co-production, and how, in its absence, partnership attempts between professionals and citizens can go awry. We will continue to explore these concepts and challenges through more insights on this blog and some practical examples from our work alongside the community of Athenry.

Guy Calvert-Lee

I love this. ABCD perfectly describes Local Ownership, which is critical for sustainability. Externally driven interventions nearly always fail once the external driver is removed, but locally owned interventions carry on for as long as the need is there.

Jim McKay

How does ABCD address external (structural and political) factors that impact on impoverished or marginalised communities?