The Paradox of the Alongsider: Serving While Walking Backwards (Part 2)

The ‘alongsider’ treats the case of ‘the un-walked dog’ in last week’s post, as an opportunity to serve while walking backwards. The way they do so – without abandoning the person they serve – is to find a more suitable person or persons than they, or another salaried stranger could be, who would relish the role to contribute.

Of course, in the real world it won’t always be possible to connect Mary to a willing reciprocal neighbour, I accept that, but, nor would it always be possible to know what external supports Mary needs, until we first know what internal supports she currently has, or in the future potentially could have. It is important therefore to recognize that the kinds of localized supports she may actually need, are likely to be disconnected.

The challenge therefore is to connect currently disconnected assets, and to do so in such a way as to meet Mary’s definition of what a good life would look like, while respecting her capacities and those of her neighbours to co-create the conditions for her version/vision of a better life to flourish. Doing so demands an asset-based community development approach in my opinion, albeit not everyone would label the process in those terms.

As noted in last week’s blog, here John, as a savvy alongsider has a few tricks up his sleeve. Firstly, he knows the person in the neighbourhood who is a full-time community animator, because he has taken time and care to cultivate a collaborative working relationship with her.

Secondly, the alongsider knows well what they and their agency can’t do. In other words they have a healthy appreciation of their limits.

All that in mind, John says to Mary, ‘I know someone who can help’, gets her permission to make the connection and then brokers a conversation in her living-room, between the three of them, with Mary in the lead. John, always presumes competency in the individuals and communities he serves, and where additional supports are needed to ensure people can share their gifts and have them received, he is happy to do the hard work needed to climb over the barriers to secure those supports. And where necessary to heckle those who put up inane roadblocks to such opportunities.

One of the things that John has learned over the years is to work with allies who are not as restricted by red-tape within the health silo, as he is. So, he’s formed very strong working relationships with embedded intermediaries, which are small local organizations, that are rooted in the local community, and are likely to continue to be so for the foreseeable future.

In Mary’s neighbourhood, John works closely with the Chambers of Commerce, local faith based organizations, arts groups and many other associations. He also works closely with the Community Animator who works across all silos and for none, because for them the neighbourhood is the primary unit of change.. They (Community Animators see Touchstone Two: Recruiting Community Animators for details) have the shortest job description you could imagine, two-words: just connect, and not for health, safety, youth, or any other predefined worthy agenda, but for community.

The Community Animator, let’s call her Dani, having been invited into the conversation and welcomed by Mary, shares her knowledge of the local community, as well as taking care to get to know Mary’s capacities, Dani through a process called a ‘learning conversation’ discovers Mary used to be a teacher and remains an avid reader, sometimes reading as many as three books a week.

Mary, Dani and John, eventually all agree this is an insider job. John leaves, Dani stays and tells Mary about a single parent family she knows with three young children, that are all dog mad. Their Mum has recently returned to work and while sympathetic to the fact that the kids would love a dog, knows she’d end up having to care for it. Mary smiles: ‘I know where you’re going with this, Dani…’

They talk out all the ‘ifs’ ‘ands’ and ‘wherefores’, and agree that a way forward is for Mary and the kids to meet daily at the local Community Centre. Separately, John, links an Occupational Therapist and Physiotherapist with Mary to support her with her mobility concerns which she raised during the learning conversation. In the meantime, John sits with Mary to support her to ask Dani to link her with a neighbour who’d be willing to drive her around the corner each day to the Community Centre.

Mary was reticent about asking for this sort of help, because she fears being a burden to her family or neighbours, in fact she fears this more than loneliness. John and Dani understand this, and in fact are well trained and so know this is a common fear. For that reason, they understand the importance of supporting reciprocal connections between Mary and her neighbours. Mary must feel valued for her gifts, not rescued or pitied. John and Dani also understand that the term loneliness is viewed as a stigmatizing label by Mary, largely because she feels ashamed at how life ‘has gotten in on her‘, and would recoil at the thought of being referred to an activity, even one she used to enjoy, or being called lonely.

John, also offers practical support to Mary around her diabetes and issues with panic attacks when she goes out. As trust grows, Dani, also learns from Mary that she does go out once a week to attend her local place of worship, and so, asks her if there is anyone else in her faith circle who would enjoy reading to children after school? When Mary says she believes there is, she asks if Mary could make an introduction to them and her wider faith circle? She also asks if Mary would support her and a local gentlemen who is interested in being involved to share the seeds of this idea.

The Insider

The outflowing of such thoughtful connections is beauty in motion, the dog crazy kids, meet Mary and few other dog owners. Now, each day after school at the local community center, where a little library has sprung up, an informal reading group is growing in number, homework is often completed and gift sharing is plain to be seen, the whole occasion is often nicely rounded of by eating a lite snack together. The kids benefit from a connection with caring adults, who help them with their homework and the adults benefit from the children taking their dogs for a walk. It takes a village to raise a child, but it also takes a child to raise a village. This is also profoundly supportive to local parents, many of whom experience incredible stress just making ends meet.

In days past the Community Centre was quite traditional in how it programmed it activities. No more will you see in this community centre, a segregated group for seniors, and another sequestered group in after-school children and so on. These groups and others are now blended and mixed in the most delightfully chaotic ways; connected in gift sharing and in the production of shared lives. And on the days Mary is not there, she is missed.

What I have just described in summary form is not an activity or a programme that Mary was referred to, instead it’s an expression of community that she belongs to, where her fellow members cannot imagine life without her. They have fallen in love with each other.

And all that, because John did not take the dog for a walk… a perfect proscription (definition of proscription: being clear about what you are not going to do as a professional, because to do so would be to displace or replace a local neighbour. Hence in practice, it is the act of serving while walking backwards).

An Insider Job

What both the community nurse and the community animator understand are the limits of what they can do in their practice as well as appreciating the limits of the institutional world. But, for all that, they also have a deep appreciation of Mary’s capacities and those of her community. They are making a choice to build a bridge between Mary’s gifts and the gifts of her near neighbours.

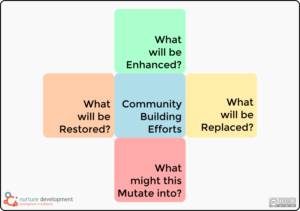

The practitioners have internalized the following questions in relation to their practice and the reach of their own and allied institutions:

Imagine what would happen if we took the practice of visiting nurses walking our dogs, to extremes. What would be replaced in terms of community capacities if all nurses and allied health practitioners could be reasonably expected to take on functions that can be, and often are best performed by local neighbours?

In the above example the community nurse and the community animator are mostly performing a support role (alongsider), while the nurse is also doing some service provision, but mainly they have facilitated community driven possibilities that previously did not exist, and could not therefore be prescribed. The term for what John and Dani did is ‘precipitate’. For more on institutional precipitation read John McKnight’s recent blog Institutional Precipitation.

Within their (Dani and John) respective institutional support roles, all progress is contingent on understanding the thresholds of what they can do unilaterally within Serviceland and, beyond those institutional thresholds, the potential of supporting community assets, which were previously disconnected, to become connected. Over and over I see alongisders guard against institutional overreach and in so doing avoid institutionalizing people, or professionally disabling them.

Like a flood acts as a negative precipitant that reveals, connects and mobilizes neighbourly care and power, these alongsiders act as positive precipitants, supporting hidden connectors like Mary, in opening the floodgates to a deep reservoir of community resources. And so, the people who were defined as the problem, or as having a problem, secure the power to redefine the problem and reveal the hidden potential of an emergent and abundant community.

So, if you’re keen on cultivating the practices of an alongsider, like I am, instead of starting with the question: ‘how can I add value to, for, or with this person?’; why not try asking: ‘how can I create the space and invite the connections between this person and their community, so that together they can co-create the things they value and that matter to them?’ To ask such a question is to take a walk in the wilderness and to wake up in the promised land, learning that more often than not, we find what we need when we connect what we have.

In the final analysis the Alongsider understands that all social progress is about the expansion of freedom, not the growth of services.

Cormac Russell

The Paradox of the Alongsider: Serving While Walking Backwards (Part 1)

Image Credit: Dog Treadmill (resized)