Part 4: We Don’t Have a Health Problem, We Have a Village Problem.

In this the last blog of the series I wish to look beyond the questions of how best practitioners can connect people back into community life; to consider how we might support communities to be health producing.

Part 1: Social Prescribing, a panacea or another top-down programme?

Part 2: Social prescription or medical proscription?

Part 3: The Importance of Asking

Community is the Smallest Unit of Health, not isolated individuals.

This blog pivots around the following quote:

“I believe that the community – in the fullest sense: a place and all its creatures – is the smallest unit of health and that to speak of the health of an isolated individual is a contradiction in terms.” – Wendell Berry

What are the challenges in considering a community as the smallest unit of health?

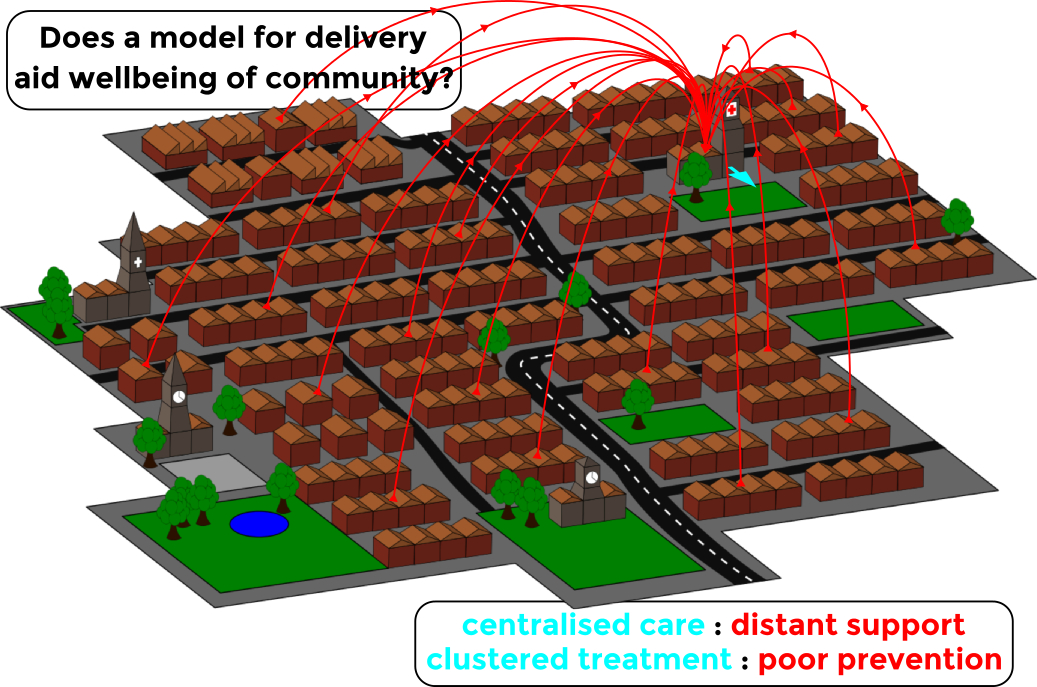

- The focus is on the individual and the system: To start, the current healthcare system is operating on a two-dimensional plane where it is primarily oriented towards the health of the isolated individuals and reforming the system.

- Community is either forgotten or an afterthought: In this two-dimensional world, ‘community’ which is a foundational third dimension of health (when considered within the context of the social determinants of health) is either forgotten or is an afterthought (‘nice to have, once we sort out the systems and services stuff’).

- When community is thought about it is thought of in extractive terms: When community it is thought of, it tends to be viewed as a place that can be tapped for its assets, rather than a place with its own health creation and production capacities, that are not services but immensely life giving. The giveaway terms which reveal an extractive mindset are: harnessing assets, harvesting assets, tapping into community assets.

- Community assets need to be discovered, connected and mobilised: The problem with treating communities as asset banks to be tapped is that communities simply don’t work like that, instead they are places with assets which are largely invisible, disconnected and yet to be mobilized. The job of public institutions including those in the third sector is therefore, to support citizens and their associations to discover, connect and mobilise those assets. Thereafter to create a dome of protection around their inventiveness, it is certainly not to displace community invention by becoming the primary inventors.

Currently, many well intentioned health reformers are by-passing the process of facilitating citizen-led discovery, connecting, and mobilisation, what I refer to as Community Building. Instead we are seeing many commissioners paying third sector organisations (who they treat as the ‘community’ or a proxy for the community) to accept referrals from clinicians and then claiming this to be asset based community development. It is not. This form of commissioning is entered into in good faith; in the belief, I suppose, that what they are doing is an innovative way of plugging the multi-generational funding deficit for community building. And perhaps more importantly in their minds, a way of going to scale across the UK and thereby reaching everyone in need.

As I read the tea leaves in the UK, my sense is that we are about to see a shift in gears around SP, from the prototyping phase (of the last 3-4 years) to more standardised and scalable models of SP. If I’m correct, this will of course be a critical phase for SP, but it will also likely have a considerable but less obvious impact on civil society and local communities. As those familiar with systems change know, you can never only change one thing. In a climate where there is little alternative funding, initiatives with funding, like SP, tend to dominate. Therefore it would not surprise if within the next 6 months we witness nearly every initiative becoming about Social Prescribing. Anyone who’s been on the funding scene for more than twenty years knows what way this particular story ends: Social Prescribing is replaced by the next new shiny idea and so the dance begins again, the steps are the same but everybody colludes in rebranding. What was always done continues, but with a name change.

Here’s an alternative way forward to the clinician/commissioner-led approach, which would integrate Clinicians efforts, around medical proscription and advocating for citizenship and civic participation, with:

- ABCD Community Building efforts at neighbourhood scale,

- Circles of Support for those who are most isolated and for whom referral is simply not enough,

- Local Area Coordination which actively advancing the ‘good life conversation’, and pushes back against case management culture in Social Work and social care,

- Personal Budgets which affords people income in place of services and choice and control around how they spend it,

- Support, and active investment/sponsoring of Cooperatives to grow local capacity to respond.

Making the Case for a Community Building Approach

In simple terms, the case for ABCD Community Building being foundational in relation to the others, is that if upward of 20% of people attending their doctors are not sick but are ‘symptom carriers’ of social or political issues, then we should seek to get to the root of those issues. This is what Public Health has sought to do for decades, as has Community Social Work and Community Development. As Bishop Desmond Tutu (paraphrasing many before him) put it:

“There comes a point when we need to stop just pulling people out of the river. We need to go upstream and find out why they’re falling in.”

If we do not directly invest in our communities: ‘a place and all its creatures’, [sic. and I would add its economy, ecology and cultures], we may one day find there is no longer a community at all. We cannot expect to engage with and refer to communities unless we first support them to be built from inside out. ‘Community’ should be understood as a verb, not a noun, in other words it is the consequence of our efforts, not a static thing at which we point or towards which we make referrals. To illustrate how I believe this more dynamic/emergent approach to community can be achieved I will share a few brief stories including:

- the inspirational life experience of Judith Snow.

- A Health Foundation that is supporting residents in Rochester, New York to become more health producing.

- A Cooperative movement in the region of Emalia Romagna.

Each of these examples emphasise the importance of community building and citizenship. They illustrate the limits of the current approach which seeks to address health issues, and champion an alternative approach which enable community health production. As I’ve already said in previous blogs in the series, one of the reasons people who are not bio-medically unwell are falling into routines of visiting their GPs, or using other services (such emergency services/social care) is because they are lonely and feeling useless. These are community issues, not clinical/medical ones, hence why the community (inclusive of those being excluded) should lead in addressing them. Hence further, why simply reforming the healthcare system so that it stops the revolving door scenario and instead redirects people back into community life, will not be sufficient and could potential be harmful. We must instead of siloed; piecemeal reforms, more fundamentally, address the root issue by also building up our communities from the inside out.

To engage in systems reform without facilitating community building at neighbourhood level, would be analogous to mono-cropping. Where the seeds are metaphors for the people referred to communities by GPs or other professionals, and the land a metaphor for the communities that are losing their carrying capacities (connect-ability) and ability to be health producing while having ever increasing numbers of people ‘many with complex support needs’ being referred to them.

All Institutional Progress is Contingent on Understanding Limits

All instruments of “Helping” have a threshold past which they cease to be effective, or worse, they become counterproductive. Hence all progress is contingent on understanding the limits of one’s intervention (Illich, Medical Nemesis). Typically, if we search them out, at the edge of our institutional competencies there are others who can do what we cannot. If when found, we honour them -in this interface between the limits of our capacities and the full potential of theirs- we can begin to form genuine change making efforts and partnerships. In many contexts, what on paper are referred to as partnership, in practice are no more than the mutual suppression of loathing, in pursuit of government funding.

Authentic partnerships can only exist when each partner brings unique assets, and irreplaceable functions to the table. The logic of partnership is that the union enables all parties to do something together that they cannot do alone, but also recognizes that each partner must have the space and support to do what they do best on their own terms. That means that as well as being clear about what it is each partner can do, we must be clear about our limits. It seems on the main that institutions are not so good at declaring their limits, but are excellent at defining the limits of the communities they serve, and thereafter asserting how they can address those needs with their institutional competencies.

Yet, one of the more fundamental limits of institutions (of which we rarely hear mention) is that they cannot command care. Take 4 minutes to listen to Prof. John McKnight articulate this and make the point that care is the freely given gift of the heart, it is not an institutional intervention or a service (though both are important), it is a consensual human exchange that cannot be prescribed. For those who linger in waiting rooms, what they need most is a life, not a service. What they yearn for is belonging: the experience of unforced and unpaid for acceptance, what most call, care. That ‘gift’, the gift of care, which cannot be bought, managed, scaled or otherwise commissioned is the antidote to loneliness and the elixir of life:

(You Can’t Command Care, Abundant Community)

Current Health systems address health issues, they rarely facilitate health production.

If care is produced through relationships, and that processes is critical to population health and the wellbeing of exiled people, how might we support the creation of a culture of care within our communities? How might we support the nurturing of communities that have a welcome for the neighbours we have exiled to surgery waiting rooms, and emergency helplines? How might we create communities that care enough to break people out of institutions and say to them:

“where have you been all this time? You matter to us, we cannot do this without you, we need you and we need your gifts. don’t worry about your fallibilities, we all have them; we’ll work with you as you are, so you can participate in own unique way and contribute your gifts on your terms, let’s go!”

This is the other side of the “what matters to you?” conversation. In practice, I can only truly answer the “what matters to me?” question, when I know I matter to others.

How do we nurture health producing communities?

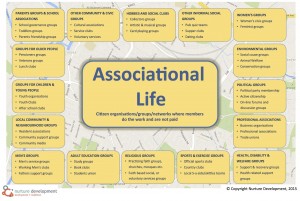

The plural of citizen is association; an association of associations that welcomes strangers constitutes a powerful and diverse community. Powerful and diverse communities are health producing.

Don’t measure the strength of a community by the capacity of its leaders, but by the depth of its associational life & how they welcome the stranger. You can do this by using this topology of associational life (above) at the beginning of the community building process and then celebrate and cheer on the quickening of associational life as it gets deeper and more connected by regularly asking: are we seeing neighbours whose gifts were not previously received participating more? Are we seeing associations driving change and feeling more powerful? Are associations in the neighbourhood sometimes coming together to talk about what they can do together, that they can’t do alone?

Don’t measure the strength of a community by the capacity of its leaders, but by the depth of its associational life & how they welcome the stranger. You can do this by using this topology of associational life (above) at the beginning of the community building process and then celebrate and cheer on the quickening of associational life as it gets deeper and more connected by regularly asking: are we seeing neighbours whose gifts were not previously received participating more? Are we seeing associations driving change and feeling more powerful? Are associations in the neighbourhood sometimes coming together to talk about what they can do together, that they can’t do alone?

Many of the people that Social Prescribing seeks to repatriate to community life have inadvertently been rendered strangers to their neighbours and home places. Hence real work is to support residents to create more hospitable communities in place of hospital beds and other such medical accoutrements. This requires processes of intention community building.

The Greater Rochester Story

If you are seeking out a model for effectively supporting community building that precipitates community led health production, look no further. The Greater Rochester Health Foundation are unique in funding urban and rural neighbourhoods to become health producing, and are doing in a way which is both groundbreaking and exemplary. The essence of what sets them apart from others is that they work on a minimum ten-year time frame and do not impose health target or predefined outputs or outcomes. To hear a full account of what is going on please listen to extensive interview with an advisor to the initiative Deborah Puntenney, (recently retired from her position of research associate professor in the School of Education and Social Policy at Northwestern University) and John McKnight and Peter Block: How Community Action Shapes Health: Full recording (57 minutes).

As part of the Greater Rochester Health Foundation Neighbourhood Health Improvement Initiative they are funding residents’ groups to recruit community builders/animators to work in their neighbourhoods to reweave the social fabric of their communities and increase collective efficacy at Block level.

The Foundation explain why – even though they are a health foundation – they are funding initiatives that some might argue fall outside their objectives, as follows:

“Our daily lives and the neighborhoods in which we live them—where we raise our families, work, and play—along with our personal health habits, affect health in countless and complex ways. Some neighborhoods support health and healthy behaviors better than others. In healthy neighborhoods, we feel safe walking outside, can access green space for recreation and physical activity, and we can purchase and eat healthy, affordable food. Healthy neighborhoods are free of abandoned housing that attracts crime and are places with trusted neighbors to turn to when in need. Neighborhood environments such as these are the vision for the grantees of the Neighborhood Health Status Improvement initiative.

Since 2008, Greater Rochester Health Foundation has supported asset-based, grassroots efforts to improve the physical, social, and economic environments of neighborhoods in the Greater Rochester area and surrounding counties.”

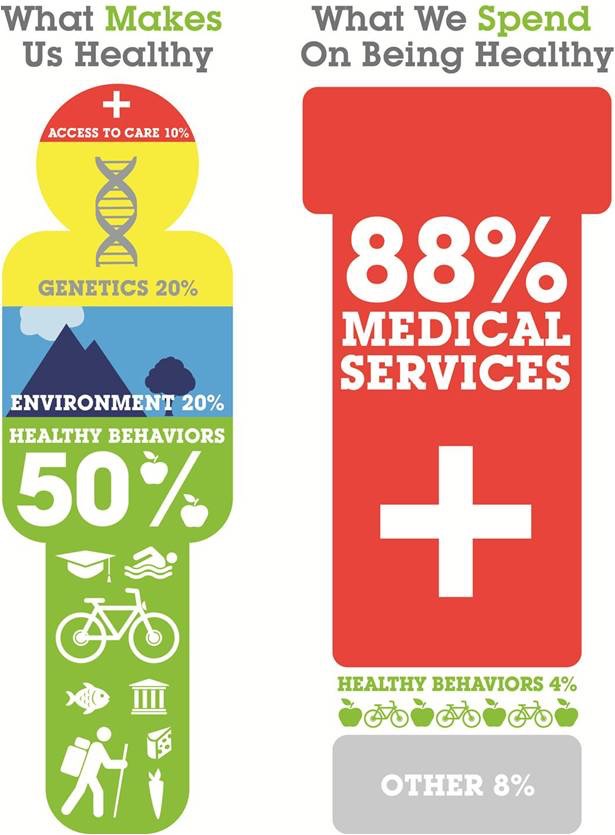

In the UK, the contrast (illustrated in the infographic below) between what makes us healthy and how money is invested in the healthcare system is stark. The contrast also provides an important marker as to where change is really needed. Health is not medical, it is political but it is also profoundly social.

(Image: What Makes Us Healthy vs. What We Spend on Being Healthy by Bipartisan Policy Center)

Emalia Romagna

In the Italian region of Emilia Romagna where Co-ops produce a third of its GDP we are seeing the new frontier of health and social care, in truth it’s been there for a long time, but nobody thought to look there before now. Emilia Romagna has a population of nearly 4.5 million people, its capital city is Bologna, and from an economic perspective it is very special. About 2 out of every 3 people are co-op members. Coops are part of the DNA in the region, and now it is beginning to morph into a new market, the provision of social services. This is the single biggest growth area for the co-operative movement in the region. Could it be with the social values of the co-op movement, its members have the capacity to create more cost effective and care-filled alternatives to more traditional large and bureaucratic institutions?

In the UK, somewhat ironically the last remaining community co-operatives are funeral undertakers. But Mervyn Eastman and other are doing something a fine job in leading a resurgence of the co-operative movement across the UK, with early expressions to be found here: Providing Care through Cooperatives – Survey and Interview Findings. The potential of movements like these are exemplified through the example of Emalia Romagna and while the context of this region is special, the potential for local expressions in the UK and elsewhere are significant.

Judith Snow

By way of introduction to Judith who with the support of her circle lead the movement in Canada to receive income instead of support, I’d like to share with you an extract from my book in which John McKnight shares he’s observations of Judith and the significances of her actions:

John McKnight: “She led the fight in Canada to get income instead of services.

And with her circle of support that she built around herself she became the first person in the province of Ontario to get an annual personal budget from the government – maybe $70,000 – to use for her own wellbeing.

Now she also is a wonderful speaker and trainer and enabler, so she makes money that way too. And as she has to have round-the-clock support, she needs more money than most people.

But after she had been on an income system for two or three years I remember saying to Judith:

“So Judith tell me how many services for a disabled person have you used in the last year? Because you are now the empirical proof of what is needed as against what professionals say you need.”

And she said:

“In the last year I have used two services that are unique to me. And one of them I didn’t want. So the first one was my very complex wheelchair. I have it because I don’t walk so it’s related to my disability and so I went to a company of mechanics who understand wheelchair technology and I went to them because I needed them.

The second service was that then every time I want to go somewhere on an airplane they insisted I talk to their disability specialist. I don’t need them but I had to go: to get on an airplane I had to go through them. But as regards all the services that I was dependent on before, I’ve used none.”

And this is a woman who is as physically dependent as you could possibly be.

So if you looked at her you’d think she might need a whole lot of compensatory stuff. But all the system did was justify itself by saying she needed this complex set of services, when what her life demonstrated was that mostly, she didn’t.

The service system needs her. She doesn’t need it.

The Careless Society, Community and its Counterfeits is pretty critical of the service system, so when people say to me, “Well, don’t you think there is some place for them {Systems}?”, my answer is yes; but when people say so.

And for people to be able to say so – what needs to happen? Systems must be prepared to say: ‘you’re going to have the income to make all the choices you need to make in a regular life’, (that’s what Judith’s income allowed her to do).

What we need is what those people need.

We never have the foggiest idea what people need until we give them those unique resources that allow them to be an active part of the community making their own choices. Then we’ll see what they need of us.

And Judith is the best proof of that. As far as she’s concerned she never uses them, (services), at all, right? Yet in the whole architecture she’s the poster child of neediness! So she is the great living example of a huge edifice that for most people is not needed at all – they just need income, access to an everyday community and the relationships there, and of course, choice.

And systems focused on people who are labelled are an alternative to choice. They say: ‘your choice is us’, right?’

Before Judith died we became very close friends and I had the pleasure of spending some time reflecting on life with her, she regularly emphasized during those conversations, the vital role the folks she employed to care for her played. She didn’t however see them so much as personal assistance, but as people who supported her to participate in community life, and she interviewed them on that basis. In fact, part of the interview involved the hopeful candidate and her going for a tour of the neighbourhood where she lived, she always knew by end of the excursion if it was going to be a fit.

She would of course have been first to acknowledge that the folks she employed did indeed support her with her primary support needs, but that was a means to an end, and the end goal for Judith was always about sharing her gifts and receiving the gifts of others in community life. I would not envy any professional that dared try to set forth a ‘worthy social activity’ for Judith. As I wrote these blog she was never far from my thoughts, in fact one evening after I read my children some stories I played them The Duck Song which is a very funny 3 minute cartoon of an impish Duck who walks up to a Lemonade stand and keeps asking for grapes, much to the annoyance of the vendor. What unfolds is hilarious and has gone viral on YouTube. As I watched it I smiled and thought that’s how Judith would have been, for her is was always about choice, control and community.

She was the embodiment of what happens when the principles and the practices discussed in this series are brought to life. For Judith, the combination of having a Circle of Support strong enough to support her to break free from the institutional world, a personal budget that enabled her choice and control, and an understanding of ABCD principles were a combined source of immense liberation.

Conclusion

The future will continue to present the consequences of social fragmentation, the carriers of those symptoms will sit in doctors waiting rooms, linger in hospitable beds, fill disproportion air time of emergency help lines, and cost Local Government Social care Directorates billions in savable resources. Until we address the root cause, Social Prescribing runs the risk of becoming the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff, driven by well-meaning but beleaguered volunteers.

Thomas Kuhn, who popularized the term paradigm shift, noted that at the edge of every dominant paradigm are new ideas that sometimes coalesce to form a new paradigm. To end on a positive note, perhaps it is possible for SP, to throw a lifeline to communities by working with the likes of Community Foundations who operate outside the medical system. So that they can begin to genuinely support the birthing of approaches like we’re seeing in Rochester. This form of ally building alongside strategic investment in supporting the resurgence of the cooperatives would I believe trigger a step change. And I’m pleased to say there are UK examples of this already afoot in Exeter for example, where I had the privilege of offering some training and advice to the Devon NHS Trust, County Council and Devon Community Foundation. So, the seeds of change are available but will scatter in the wind unless we stop pulling people out of the river and start to address the subsidence of the ground under our feet.

It time to awaken to the fact that we don’t have a health problem, nor a social care problem, nor a youth problem, nor even a safety problem, we have a village problem. In our heart, we know the solution to each does not lie in reforming silo by silo but in organizing our silos the way people organize their lives, so that the neighbourhood becomes our primary unit of analysis and change. This could lead to genuine placed based working, pooled budgets, and the release of resources to work upstream and stem the subsidence of our social fabric which is causing people to fall into the river quicker than we can pull them out. If it does here is a framework for precipitating the resurgence of community and a culture of care, which we have developed over the last 21 years by learning from communities in 35 different countries: 7 Top Tips for Citizen-driven Community Building. Nothing would make me happier than to see people run with it and make it a reality where they live.

Thank you for reading this blog series and for your reflections, whether shared or otherwise; here’s to your health and wellbeing.

Cormac Russell

sarah mcdonald

Really interesting series, thank you. I share your concerns. There seems to be too little change in the power dynamics – CCG s can decide to fund social prescribing, but inevitably will decide not to fund it and move to the next shiny intervention, as has happened with peer support. Plus, love the point about where will the strong, well resourced community associations to be ‘connected’ to be?