You measure best when you treasure first

Over the last six months I’ve been using an app on my phone, which counts the steps I take each day, like millions of other people around the world it is set to a target of 10,000 steps per day. It’s actually helped me be more intentional about walking a reasonably substantial amount every day, and I intend to continue using it. That said, I shocked myself yesterday morning. I was in a hotel on my way down stairs for breakfast. Standing in front of the elevator, I thought to myself, ‘hang on, use the stairs’, then to my surprise I actually thought, ‘no, there’s no point, I don’t have my phone, so the steps won’t count’. So at some level a part of my mind was subconsciously locked into the belief that if my steps are not registering on my app, they don’t count. I immediately saw the nonsense of my line of thought and hightailed it down the stairs.

But as I ate breakfast I was struck by my behaviour and wondered if this line of thought is similar to what happens when measurement of community initiatives go wrong?

We all like to know that what we’re doing is having impact. This is as true in our civic efforts as it is in our personal and work lives. Understanding one’s impact or the impact of collective effort is as important to residents as it is to those who may be funding some of their community building endeavours.

Still so often the very things we measure, how we measure them, and who is doing the evaluating, can result in quashing the very thing we’re trying to measure. Some forms of measurement undermine:

- Participation

- Shared responsibility

- Belief that everybody’s contribution matters

- Grouping behaviours that build a sense of collective agency.

These negative consequence that add up to a retreat from active neighbouring are largely the result of measuring gone wrong or at least measuring the wrong things. Too often measurement of community initiatives takes the form of auditing instead of learning and is initiated and owned by the donor, not the people who are co-creating the homemade and handmade effort. Such approaches to measurement also overly focus on and overestimate the contributions of paid staff and named civic leaders. Which is demoralising for other residents whose efforts are inadvertently made to seem marginal by comparison. Hence why sometimes the very act of measuring community efforts can destroy them.

So, can we or should we measure anything when it comes to citizen led action? The answer is, it depends. But more straightforwardly: yes there are things worth measuring and when we value them they can grow, circles of participation can widen, inclusion and diversity deepen.

The dilemma of measurement as described above rightly surfaces anxiety in residents and ethical practitioners. Mindful of the potential of the unintended consequences that traditional forms of evaluation create, the savvy resident and practitioner will use that anxiety to ensure citizens lead the process and that it is one based on learning, not auditing or telling the funder what we think they want to hear.

Learning from these savvy folk we know that there are a number of ways out of this measurement bind. Simple ways, but ones that take courage to negotiate and implement. Here are four ways that can help us avoid killing the very thing we measure:

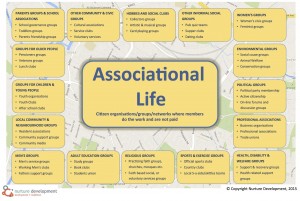

- Don’t measure the strength of a community by the capacity of its leaders, but by the depth of its associational life & how they welcome the stranger. You can do this by using this topology of associational life at the beginning of the community building process and then celebrate and cheer on the quickening of associational life as it get deeper and more connected by regularly asking: are we seeing neighbours whose gifts were not previously received participating more? Are we seeing associations driving change and feeling more powerful? Are associations in the neighbourhood sometimes coming together to talk about what they can do together, that they can’t do alone?

- Ensure that the impacts that are being measured are what people in the community say they want to measure and enable them to do that in a way that is fun and useful to them. If a donor requires different measures then find a helpful person who understands ‘institutional’ requirements and culture to do that work, but ensure it’s someone who also knows how to enable the Community to share their learning and the impacts that are of value to them. This could be important in the longer term if donors are to learn how to invest well in citizenship and community driven efforts. Communities have the power to teach donors, funders and commissioners how to treat them. Telling the community story in this way becomes an expression of power but also affords outside donors the opportunity to be more impactful in precipitating asset-based community driven efforts next time, thereby creating a win-win. We have found evaluation methodologies like Developmental Evaluation, Most Significant Change and Realist Evaluation very helpful. When it comes right down to it there’s a lot to be said for good old fashioned reflective practice with citizens in the driving seat, with some thoughtful gentle company from practitioners who know how to facilitate and not take charge. Here are some of the example of the evaluations that have been done around our work with residents across the UK: Nurture Development Reports.

- You measure better when you treasure first. Because we’re measuring the impact of our community building efforts by learning more about how relationships deepen between neighbours, how the culture of community is nurtured, how the environment and the local economy are effectively stewarded, the learning needs to be in the hands of the community, not consultants, evaluators or outside donors. This is not a numbers game. Relationships are the currency of community work, not data or money. Hence the preferred process is one that values what goes on between people, not what goes on within them as disaggregated individuals. It is not therefore about counting numbers of people who show up, but about cheering on the participation and contributions that deepen community life. Most of the things that matter most in life are meant to be treasured, yes of course sometimes measuring them is of value, but not always. We need to do a better job of discerning the difference. One of the areas worth being intentional about, what some have traditionally thought of as measuring, is around how well we are doing at welcoming the stranger at the edge of our community life. This involves asking: ‘how many people who are vulnerable to not having their gifts received are now in interdependent, reciprocal relationships, as a result of our shared efforts?’ I would say that this is more about accountability than measurement, but certainly if each week we note that no one or very few who’ve been previously exiled from community life are getting in on the action, that certainly poses an important challenge.

- Finally, nobody likes to be audited, even people who are legally obliged to ensure their business governance is in check get particularly jittery around audit time. While auditing businesses, public sector bodies and charities is critically important for good governance, we would never audit our friends, partners, or children (not out loud anyway). Picture the scene, someone asks you, ‘Do you love your partner?’, ‘Yes!’, you reply. To which they respond, ‘OK but how much; quantify it for me!’ At which point I suspect you’d walk away. But somehow society reckons it is appropriate when it comes to community efforts to audit their relationship building endeavour. The problem with the auditing system, aside from being heavy handed and the wrong tool for the job, is that it uses summative and formative methodologies which effectively measure whether throughout the life of the initiative whether you did what you said you would at the start. In so doing it mitigates against mid course correction, learning, growth and change. Because community work is iterative, relational, messy and emergent many of our current evaluation tools simply do not work, and some are even harmful.

There are many things in life worth valuing deeply, some of those things are worth measuring, but many are not, lets ensure the things the are of most importance like learning, going at the speed of trust, figuring stuff out together are not discounted in an effort to capture the quantitative data. There is merit in counting how many people knew how many neighbours by first name on their street when a process of community building commenced. And then with that as a baseline, after community weaving has seasoned, measuring again to see what’s changed. Measures like this alongside the measure of associational life and the reconnecting of those who’ve been marginalised, have a way of helping local people stay accountable to each other and to their community building efforts and principles. Savvy donors will ensure they organise their reporting requirements in such a way that they amplify that learning, and cheer on deepening practice. If you’re reading this as a funder, or donor it would be worth checking out the McConnell Foundation and the Nebraska Community Foundation as examples of funders who have done a good job of coming alongside communities in a way that emphasises the unearthing of community treasures, and then figuring out best means of measuring those.

In sum, you measure best when you treasure first. Now I’m off for a walk, without my phone.

Cormac Russell