Free, Prior, and Informed Consent – Part 5 of 5

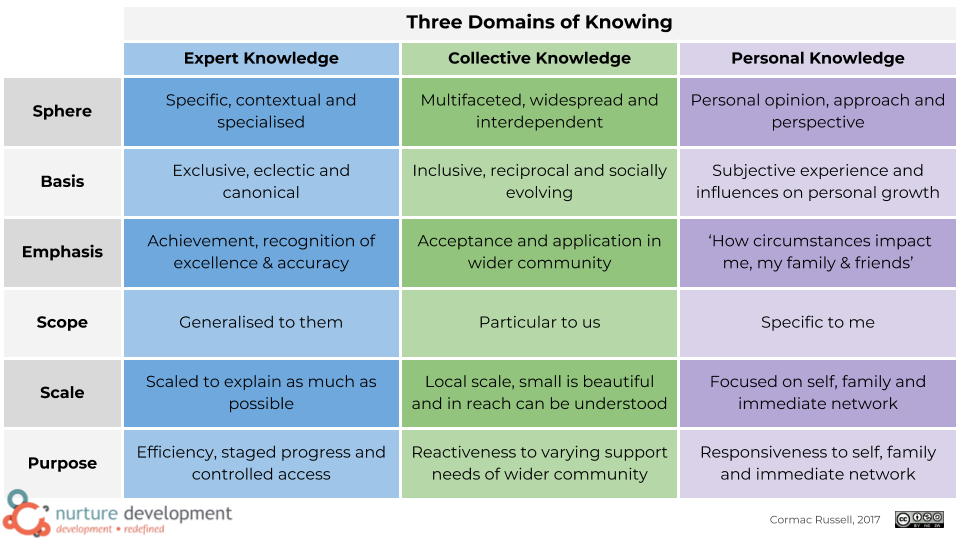

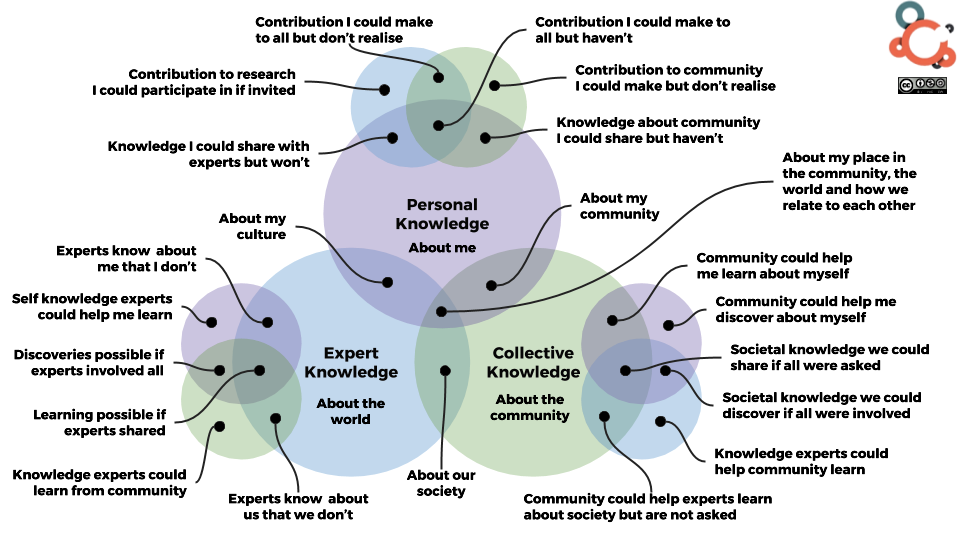

In the previous 4 blogs in this series I looked at what I’m calling the three domains of knowing: Expert Knowing; Collective Knowing and Personal knowing, and how they can best relate to each other.

For these domains of knowing to work well together there needs to be a commitment by all involved to the wellbeing of the community, as a whole. That requires ongoing attention to power and how it can be used to work against the interests of the whole and well as for it. And how best to negotiate that power balance is the focus of this post.

The renowned Sociologist Max Weber in his defining work, Economy and Society, identified three ideal types of legitimate rule, across history (in that most tacitly accept such authority up to a point):

- Charismatic Authority (leader as hero, claiming spiritual or moral character status)

- Traditional Authority (feudalism, patriarchs)

- Legal Authority (bureaucracy, rational legal authority)

There are few pure expressions of any of these types of authority, but they provide a useful reminder of how power can be held within society and how it shifts from autocratic to bureaucratic over time in liberal democracies. Weber noted that nation states generally progress from 1 to 3 as more rational legal authority becomes dominant. Hence, modern liberal democracies operate primarily from the rule of law/legal authority. But behind this legal authority are a set of experts with special understanding of how this power can be upheld, deployed and when necessary circumnavigated.

Therein lies the problem and the potential, if we are to avoid having a technocracy (rule by technocrats) we need to proactively ensure that this authority remains at the service of citizens who are enabled to act powerfully together. One would be forgiven for thinking this is already in hand, after all much ado is made about the importance of professionals operating to the highest standards, and ensuring citizens know their rights and how the systems that serve them work. Yet, for all that, time and again we see an imbalance in the relationship between designated experts, communities and individual citizens.

While there is much reason to celebrate advancements in the various social contracts and commitments to uphold the rights of individuals who receive service, I believe more is yet to be achieved.

Here are three ways greater harmony can be achieved across the three domains of knowing:

- Instate the principle of Free, Prior, Informed, Consent (FPIC) as widely as possible

- Obligate institutions to establish how they are fulfilling the principle of subsidiarity.

- Support community building at hyper-local level.

Free, Prior, Informed, Consent.

In both legal and medical professions practitioners are expected to do all they can to gain free, prior and informed consent (FPIC).

Free: consent given voluntarily and without coercion, intimidation or manipulation. A process that is self-directed by the person from whom consent is being sought, unencumbered by coercion, expectations or timelines that are externally imposed.

Prior: consent is sought sufficiently in advance of any authorisation or commencement of activities.

Informed: nature of the engagement and type of information that should be provided prior to seeking consent and also as part of the ongoing consent process. In plain English, a second opinion is encouraged.

Consent: decision made by the person to consent or withhold consent.

This process obliges the expert to communicate in the clearest of terms and at the highest ethical and legal levels. Yet few would argue that it is anything other than a baseline standard of how we would expect an expert to show up in our lives given when the stakes are high, after all if a surgeon is about to operate on me, my life is literally in their hands, the same goes for legal advice. Advice from a legal practitioner can precipitate life altering circumstances, which make the principles of FPIC essential.

This line of argument should not stop there. Surely all professionals who have access to canonical knowledge and use it to advance a recommended course of action should be obliged to use FPIC or offer valid reasons why they are not? Too often consultation is presented as the only standard by which citizens and individuals or as a collective can engage in deliberation with institutions.

The inadequacy of consultation as a way of transferring ways of knowing across the three domains and reaching equitable decisions, is most apparent in instances where extractive industries (e.g. Mining) negotiate with indigenous communities. Fortunately, the United Nations Human Rights, Office of the High Commissioner have rightly stepped in to legislate for the weaker of the two parties in such negotiations: the community.

Normative foundations of the requirement for free, prior and informed consent

The principle of free, prior and informed consent is linked to treaty norms, including the right to self- determination affirmed in common Article 1 of the International Human Rights Covenants. When affirming that the requirement flows from other rights, including the right to develop and maintain cultures, under article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and article 15 of the International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (ICECSR), the treaty bodies have increasingly framed the requirement also in light of the right to self- determination.

Placing the highest ethical and legal standards on the more dominant of the two parties, namely the extraction companies. This gives the community a fighting chance and ultimately the right to say no with the full protection of the law behind them. The catch of course is that the relevant state must ratify the law thereby bringing it into their own statues, before it can have any teeth.

The UN regulations stipulate that as well as free, prior, and informed decisions, that consent must be through a process of collective decision making, made by the right holders of the land and reached through, a customary decision-making processes of the communities. To my mind this stipulation is incredibly important, given that indigenous communities have very particular and nuanced ways of making decisions.

I am generally quite doubtful of the influence that top down legislation can have, but this sort of legislation can be incredibly useful in mitigation the imperial impulses of institutions and experts.

The Principle of Subsidiarity

Another way to positively mitigate power and spread it more evenly across the three domains is to actively legislate for the principle of subsidiarity, whereby no larger, political, social, institutional entity will do that which a smaller entity can. Legislating in favour of smaller more localised efforts creates the space for personal and collective knowing and inventiveness to grow and take root by ensuring it is not undermined or overwhelmed by a bigger entity. Not instating such protections is tantamount to governments defacto siding with big business and large institutional frameworks over the sovereignty of citizens. Thereby legislating for technocracy (rule by technocrats) in preference to democracy (demos=the people; kratia=rule/sovereignty)

The importance of Community Building

Ensuring that personal and collective knowing can flourish must be the primary objective of a flourishing self conscious democracy. After all an outside professional cannot effectively or affectively engage with a community if citizens have not first been afforded the protections and enabled to engage with each other, through free association and collective bargaining for example. Free, prior, informed consent and subsidiarity assumes that communities have been supported to make the transition from being consumers to being citizens. It’s an assumption we can’t afford to make. Instead we must be prepared to invest in supporting people to find ways of knowing each other and deliberating together at grassroots level, that process start with respect for what is already in place in communities. Not alone do our democracies depend on it, but so too do our institutions and the people who work within them.

In the final analysis there are three questions that must come center stage in ensuring harmony across the three domains of knowing. And they are:

- What are the irreplaceable functions of community?

- How can experts and other professionals listen better for these functions and ensure they do not overwhelm or undermine them?

- What is it that institutions can do with and for communities that intentionally place communities in pole position as the primary inventors of a better democracy, with professionals there to serve?

These questions must both haunt us and excite us in equal measure, as we figure out how to get better at being human together. The virtue of so doing lies in the potential that it will open-up before us:

The above illustrates the untapped reservoir of potential that lies out ahead of us as human beings if we can come to know and practice better ways to be in right relationship with each other across the three domains of knowing: 1) Expert knowing; 2) Collective Knowing; 3) Personal knowing.

The above illustrates the untapped reservoir of potential that lies out ahead of us as human beings if we can come to know and practice better ways to be in right relationship with each other across the three domains of knowing: 1) Expert knowing; 2) Collective Knowing; 3) Personal knowing.

Cormac Russell

Part 1: Three Domains of Knowing

Part 2: The Shift from Expert to Collaborator

Part 3: No Experts in Matters of Judgement

Part 4: Personal Knowing: I know I need you and that you need me too

About the diagram: Knowledge Graph Key, Euler Diagrams.