Beyond Good Intentions; Towards A Good Life

Open Letter to Rachel Adam-Smith and her Social Worker

When did we stop believing that ‘It takes a village to raise a child’? When did asking fellow community members for assistance in special needs parenting (or any parenting) become a potentially harmful act? And why would a social worker believe that a mother asking for the support she needs to keep her daughter safe is a demonstration of irresponsible parenting?

Rachel Adam-Smith is a UK blogger who is also a law student, patient with congenital heart disease, the daughter of a mother who has muscular sclerosis and she is the mother of a 15 year old daughter who has severe disabilities including autism.

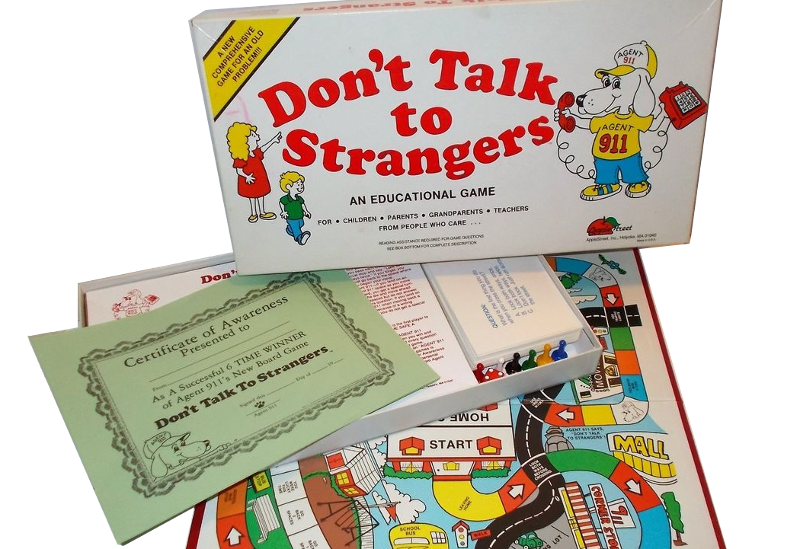

Recently, Adam-Smith penned a blog post describing how the social worker assigned to her case did not believe she should seek assistance from strangers when her daughter became physically unmanageable during emotional meltdowns that occurred in public. The social worker maintained that Adam-Smith’s daughter might not understand that talking to strangers is a bad thing. Rachel Adam-Smith is a petite person with a serious heart condition. She is a single mother. She is economically isolated. When Adam-Smith’s daughter has a meltdown, she falls to the ground or tries to run away (including into traffic). She is always with her daughter when she asks others for help.

Recently, Adam-Smith penned a blog post describing how the social worker assigned to her case did not believe she should seek assistance from strangers when her daughter became physically unmanageable during emotional meltdowns that occurred in public. The social worker maintained that Adam-Smith’s daughter might not understand that talking to strangers is a bad thing. Rachel Adam-Smith is a petite person with a serious heart condition. She is a single mother. She is economically isolated. When Adam-Smith’s daughter has a meltdown, she falls to the ground or tries to run away (including into traffic). She is always with her daughter when she asks others for help.

What are we to make of the idea that seeking emergency assistance from neighbours or community members is innately dangerous? Should we conclude that it’s equally risky to offer help to a vulnerable person who is clearly in distress?

I speak as the mother of a young man with severe disabilities and Cormac as a leader in asset-based community development. Here’s what Cormac Russell and I would say to Rachel Adam-Smith and to her social worker:

Dear Rachel Adam-Smith

You are not alone. In your community, there are many people who want only the best for you and for your daughter. They would like to help you – not only in times of crisis, but as loyal friends and supporters. The next time you ask for assistance from a stranger (and we hope you will continue to do this, because it is the safe and sensible action to take and we believe your instincts and experience will guide your choices), ask if the stranger would like to join you for coffee. Ask if you might drop off a thank you gift at their place of employment. Or ask whether you could write a note of appreciation to their employer praising the stranger’s kindness and character. Look for opportunities to transform the kindness of strangers into authentic friendships. After all, no one knows better than parents of vulnerable children that it is our caring relationships that keep our children safe and secure.

With very best wishes and gratitude for caring members of your community, who extend a hand of help and kindness,

Donna and Cormac

Dear Social Worker

You are doing your best to help Rachel Adam-Smith and her daughter. You are trying to keep them safe according to all you’ve been taught in your field of study and work. We believe that your advice to Ms. Adam-Smith reveals a problem with the way we think about ‘help’ and ‘safety’ in our society. We would like to propose an alternative way of thinking.

Traditionally, help is thought of as keeping people out of harms way, and safety is understood as preventing bad things happening. This mind-set, is so endemic in Western culture that these ways of thinking have become certainties. We no longer question them.

But question them we must. Because when our efforts to keep people safe actually separate them from natural support networks and make them less autonomous and more dependent on salaried strangers, those efforts to help can become counterproductive and harmful.

In other words our efforts to help can produce the opposite of what we intend; they make people more unsafe, not safer.

The question then, is how do we make that shift from risk aversion to liberation? For Social Work as a profession there are four necessary changes in our opinion:

- Shift the profession en mass towards Community Social Work and away from Case Management Social Work. Measure success on the basis of how interdependent at the centre of their communities the people who are being served have become, not how dependent on professional support, support that in reality is quite limited. And when that professional support ends, only the community remains (which is why we should focus on strengthening those ties for everyone, especially vulnerable people).

- Change what Social Workers are afraid of. We all carry some fear as professionals. So let’s make sure if we are going to live with that stress, we choose the right things to be afraid of. Fearing that I won’t meet my Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) this month. Or fearing the unpredictability that comes with the new relationships with individuals you serve when you work in a community way – these are counter-productive fears. They increase unhealthy stress within practitioners generally, and they stifle and disable those we serve. Useful stress comes with the fear of what might happen if I displace natural indigenous support in order to cover my back or meet my targets. Or if I make people dependent on a system that cannot provide ongoing love and mutuality without the hidden cost of unintended institutionalization and loss of autonomy. These are fears worth having, and they are real.

- Include Safety II thinking in how Social Workers are trained to think about and work with safety. Professionals in the field of Airport security are at the cutting edge in thinking about safety. They have identified two main ways that folks think about Safety. Safety I (the dominant way of thinking about safety) aims to stop bad things (things as imagined in the future) from happening. Safety II, aims to optimize the potential of good things happening based on what actually happens in the present and optimizing what’s strong not wrong from there. We need both, but our Social Workers and wider society need exposure to the Safety II mindset if we are to restore balance and common sense.

- Finally, we need to ask different questions. Instead of asking what will my intervention prevent, ask ‘what will it produce? What kind of person will be produced as a result of my advice or intervention? Systems could ask: What type of person does this ‘supposed’ productive process/advice, produce?’ We say ‘supposed’, because until we know the answer, we can’t know if its productive, non-productive or counter-productive.

When institutions develop processes that degrade the human capacity, inventiveness and autonomy of a person/persons they serve, it is mostly done with good intentions. We must learn to become wary of Good Intentions, because as we all intuitively know, the road to a life of disconnection, loneliness and misplaced fear is paved with them, especially for those most vulnerable to not having their gifts recognized or received.

With best wishes and hope for a more community-based future for all,

Cormac and Donna

Donna Thomson and Cormac Russell

Donna Thomson is the parent of a young man who has severe disabilities. She is the author of The Four Walls of My Freedom (House of Anansi Press, 2014), blogs frequently at The Caregivers’ Living Room (www.donnathomson.com) and consults to government and health care institutions on issues relating to family caregiving.

Claudia Roodt

Absolutely agree. Could not have put it better. I am a social worker for 29years and have had the same arguement here in cape town south africa. Work with the community – not alienate them. The child and mother feel more safe with the aunty down the road than in a shelter where retraumatisation happens.