7 Top Tips For Supporting Citizen Driven Community Building – Part 3

“Love once, love always”

– George Eliot, Silas Marner

In the first two blogs of this series, we explored the importance of finding a trusted local association who can work closely with an initiating group of local residents; supporting them to make the invisible visible. This week’s blog searches for a better understanding of the pace at which asset-based community development efforts unfold and how outside support agencies can get in sync with the varying rhythms of communities.

Top Tip #3: Effective community building goes at the speed of trust.

The link between last week’s blog and this one can be summed up as:

Conversations between local residents that unveil and productively connect community assets, are not meant to be measured, they are meant to be treasured.

Trust flows from the experience of being treasured (recognised for your gifts, while being accepted with your fallibilities), not measured. When we treasure someone or something, it is the opposite of miserliness, hence why we do not think of people who treasure someone as parsimonious. One of my favourite novels is Silas Marner (George Elliot, 1861). As the story goes, Silas, a member of a small Calvinist community in England, is wrongly accused of stealing his faith community’s savings. He leaves in shame; his reputation in tatters and the woman he was about to marry choosing to marry the very man who framed him. On arriving in another (more urbane village somewhere in the Midlands, he becomes inward and reclusive, obsessing about his gold and going deeper into despair. His days are spent counting his gold and hiding it, exhibiting all the characteristic of a miser. Eventually it too is stolen and he is left bereft.

But then Eppie -a child orphaned through a series of tragic circumstances- comes into his life. He grows to love Eppie and, through her, connects with the village at large, who help him raise her as his own. She too grows to love him, so much so that when she is offered a life as the child of a gentleman and lady, by a local well to do couple (the gentleman was in fact, her father, who up to then had hidden the fact) she turns them down. Silas and Eppie treasure each other. They share a trust and love that is abundant. The more they give away, the more they have.

The three life stories of Silas Marner are instructive. In his ‘first life story’ he is in a community where trust is weak. His best friend is the man who sets him up and his congregation damns him on flimsy grounds. The lady he is to marry rejects him out of hand, and so he is used and rejected by the very people he loves and trusts.

In his ‘second life story’, in order to cope with having been betrayed and let down by those he loved in his first experience of community, he moves to a new village, where nobody knows him or his story. He falls in love with something that can’t reject him, namely his gold, but nor can it love him back. In so doing, he lives through a cycle of ever deepening dissatisfaction, as a miser, pursuing satisfaction through materialism in an effort to avoid the necessary risks associated with interdependence with community life and relationships with friends and family. His first life story, which casts him as an open, affable and trusting character, is exchanged for a new story, an individualistic, consumeristic life of quiet dissatisfaction.

Silas’s first two life stories, when combined, are an allegory and indeed a composite of the stories of everyone and anyone who has been raised in a shame-based community: defined by the labels of others and not recognised for their gifts, skills and passions. It is also a parable of a sort, speaking to the challenges of transitioning from the parochial and cloistered worlds of small inward looking communities to industrialised, anonymous environments. Of course fleeing from the judgments of nosey neighbours and harsh shaming environments to the ‘city’ of secret spaces and private places, where the primacy of the individual is beyond question, comes with many tradeoffs. Still, if you have experienced rejection from your village then the call of the ‘Big Smoke’ is an alluring one.

What is essential to note here is that neither of the first two stories offer a definitive description of reality per se. They are instead, versions of reality, fictions if you like. All stories to one degree or another are heavily laced with fiction.

Neither story speaks of the experiences you expect to encounter in a trusting community. Like Silas, throughout our lives we are the subjects of multiple stories. In some we are ‘cause’ (agents) and in others we are ‘effect’ (victims). In Silas’s first story, he is cast as both a member of his community and a victim of his community’s poor judgment. In the second story he becomes radically individualistic, with no sense of belonging to the community, having foreclosed on his previous desires to be rooted in a place and deeply connected to the people who reside there.

From this hyper-individualised position, he becomes obsessed with his private property, most particularly his gold. Like JRR Tolkien’s character Gollum in The Lord of the Ring, who refers to ‘the ring’ as his ‘precious’, Silas is consumed by the gold that he has amassed, in much the same way as extreme consumerism can result in the consumer being psychologically consumed by the products they acquire and the money they use to acquire it.

Like Gollum’s relationship to the ring and Silas’s relationship to the gold, the consumer too becomes addicted to the goods and services that the marketplace offers. Addiction nearly always results when we expect goods and services which are necessarily limited and unsatisfying to take the place of relationships and community. The more desperate we are that ‘the ring’ takes the place of one’s lost love and/or ‘the gold’ takes the place of the respect one yearns for from a community of peers, the more addicted and dependent we become. The more addicted we become on that which can never love us or respect us, the more depressed and isolated we find ourselves and so the deeper we fall in addiction.

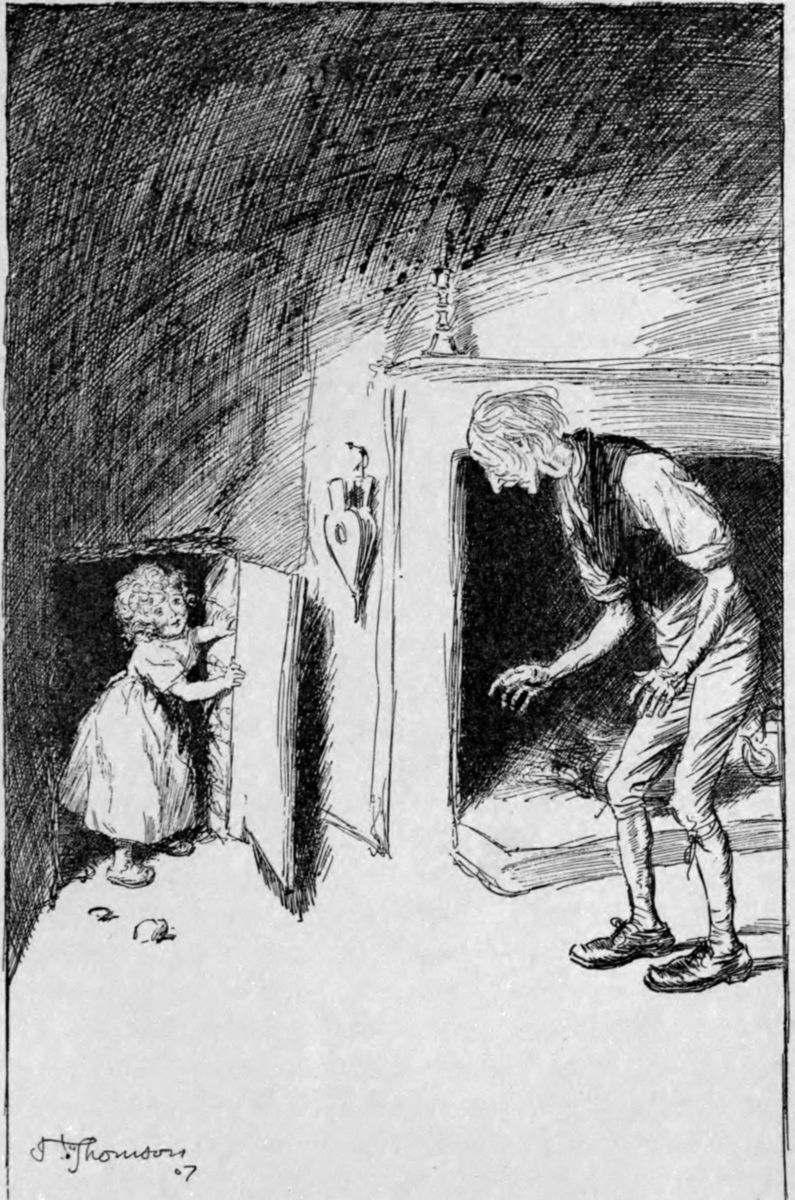

Fortunately for Silas, a stranger from the edge of the community where he had fled to, arrives unannounced into his miserly existence. She was able to find him because he too is at the edge. She arrives in the guise of a little girl called Eppie, whose opiate addicted mother had died in the snow. Eppie was the daughter of a ‘well to do’ gentleman of the village, who was hiding her existence and the fact that he was married to her mother, a woman of supposed low standing, from a neighbouring village.

The death of Eppie’s mother was most convenient for her father, who is now free of his ‘shame’ of marrying someone below his social standing. The arrival of this little girl on Silas’s doorstep is the beginning of his third life story and ultimately his liberation. Eppie loves Silas unconditionally as does he love her.

Throughout Silas’s three stories, there is an invisible determinant at play and that is trust. Silas gave trust freely in his first life’s iteration, but did not enjoy an adequate return. In his second chapter he withheld trust, and hid his assets for fear they’d be stolen, and yet that is precisely what happened. His risk aversion makes what he fears more likely. Accordingly his distrust of people deepens.

Leonard Cohen in his 1992 album The Future offers us a powerful set of lyrics from his song “Anthem,” which illuminates what happens next for Silas, as Eppie enters his home and his heart:

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack, a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in.

Silas’s third life story teaches us that trust is environmental and cultural not just personal or even interpersonal. The third version of his story was not just about his relationship with Eppie but also about how it took a village to help him raise this child. In turn how Eppie becomes the child that animates the village and transforms it into a place with a community culture. Eppie, the stranger at the edge, becomes the light, Silas was the crack that let the light come in, and the wider community came round to keep the flame alive.

Every human community is made up of people with stories similar to those of Silas Marner’s, but community building struggles in the context of closed inward communities, with defined in-groups and out groups, as much as it does in contexts that are hyper-individualised and consumerist environments. Hence, for a culture of community to hatch there must be some precipitants, that open up the heart of the place, makes visible the invisible, and creates a welcome for the outsider. Occasions such as flooding or other natural disasters offer powerful glimpses of community potential, but such upsurges of restorative efforts should not be confused with the birth of a culture of community and inclusion.

Giving life and long-term investment to welcoming and powerful communities, calls for a willingness to create permeability in our personal and association’s lives. As with Silas, that takes time. Each of his three stories can be understood as one story, the story of how he learned to travel at the speed of trust. Thought of this way, we can see that the three stories weave together to form a passage through which Silas journeyed and learned:

- How to build reciprocal relationships

- Connect with supportive associations

- Build life-giving relationships with and within his local economy, and to re-embed the economy into the local community.

- How to take risks and create a space at the edge of his ‘almost-closed’ world to actively welcome the stranger (Eppie) into his midst, and to celebrate her difference and the diversity she created.

- How to say to other members of the community: “if I am to raise this child, I need you, I can not do this without you”. It takes a village.

- How to recover from his addiction by discovering the power of community connection.

- How to become rooted and invested in the ecosystem (in the environmental and cultural sense of the term) of the place where he and Eppie live.

- How to go beyond the victim narrative with all it’s helpless/hopeless talk, and retributive pursuits of faux-justice, to a restorative sense of self and others. In short he moved from the victim and consumer narrative to citizen and contributor narrative. Accordingly he became defined not what he allegedly stole, or amassed or consumed but by contributing to the wellbeing of the community.

Liberating a community culture to call these characteristics forth from local residents takes decades, not years. It goes at a generational speed, not a funding or an election cycle. Hence those who think that they can measure the growth of community culture with key performance indicators (KPIs) are as misguided as Silas was when counting his gold. We can only hope they see that Eppie is on her way trudging through the snow to remind them if they are focused on efficiency, measurement and scale while receiving salaries for building community, they have lost their focus and purpose. Silas Marner teaches that as trust deepens, a culture of belonging takes root.

Community will never be built faster than the speed of trust, and will never be stronger than the person who experiences the least sense of belonging. For me that begs the question: ‘can we create the ‘Eppie-effect’ in our neighbourhoods?’ I believe we can, and we will deal with that in a lot more detail in later blogs. For now, let’s conclude by turning to Peter Block’s book Structure of Belonging for some inspiration around how to build trust at a community level. The five conversations for structuring belonging according to Peter are: possibility, ownership, dissent, commitment, and gifts.

Possibility Conversation

The distinction is between possibility and problem-solving. Possibility is a future beyond reach.The possibility conversation works on us and evolves from a discussion of personal crossroads. It takes the form of a declaration, best made publicly.

The Questions

- What are the crossroads you are faced with at this point in time?

- What declaration of possibility can you make that has the power to transform the community and inspire you?

The Ownership Conversation

It asks citizens to act as if they are creating what exists in the world. The distinction is between ownership and blame.

The Questions

For an event or project:

- How valuable an experience (or project, or community) do you plan for this to be?

- How much risk are you willing to take?

- How participative do you plan to be?

- To what extent are you invested in the well-being of the whole?

The all-purpose ownership question:

- What have I done to contribute to the very thing I complain about or want to change?

The questions that can complete our story and remove its limiting quality:

- What is the story about this community or organisation that you hear yourself most often telling? The one you are wedded to and maybe even take your identity from?

- What are the payoffs you receive from holding on to this story?

- What is your attachment to this story costing you?

The Dissent Conversation

The dissent conversation creates an opening for commitment. When dissent is expressed, just listen. Don’t solve it, defend against it, or explain anything. The primary distinction is between dissent and lip service. A second distinction is between dissent and denial, rebellion, or resignation.

The Questions

- What doubts and reservations do you have?

- What is the no or refusal that you keep postponing?

- What have you said yes to that you no longer really mean?

- What is a commitment or decision that you have changed your mind about?

- What resentment do you hold that no one knows about?

- What forgiveness are you withholding?

The Commitment Conversation

The commitment conversation is a promise with no expectation of return. Commitment is distinguished from barter. The enemy of commitment is lip service, not dissent or opposition.

The commitments that count the most are ones made to peers, other citizens. We have to explicitly provide support for citizens to declare that there is no promise they are willing to make at this time. Refusal to promise does not cost us our membership or seat at the table. We only lose our seat when we do not honor our word. Commitment embraces two lands of promises:

- My behavior and actions with others

- Results and outcomes that will occur in the world

The Questions

- What promises am I willing to make?

- What measures have meaning to me?

- What price am I willing to pay?

- What is the cost to others for me to keep my commitments, or to fail in my commitments?

- What is the promise I’m willing to make that constitutes a risk or major shift for me?

- What is the promise I am postponing?

- What is the promise or commitment I am unwilling to make?

The Gifts Conversation

The leadership and citizen task is to bring the gifts of those on the margin into the center. The distinction is between gifts and deficiencies or needs. We are not defined by deficiencies or what is missing. We are defined by our gifts and what is present. We choose our destiny when we have the courage to acknowledge our own gifts and choose to bring them into the world. A gift is not a gift until it is offered.

The Questions

- What is the gift you still hold in exile?

- What is something about you that no one knows?

- What gratitude do you hold that has been gone unexpressed?

- What have others in this room done, in this gathering that has touched you?

Conclusion

The purpose of going at the speed of trust is not to transform citizens of a place in clients of a service system, but to build community, and community is not built at the speed of an election cycle or a funding cycle.

“In old days there were angels who came and took men by the hand and led them away from the city of destruction. We see no white-winged angels now. But yet men are led away from threatening destruction: a hand is put into theirs, which leads them forth gently towards a calm and bright land, so that they look no more backward; and the hand may be a little child’s.”