Communities are the atomic elements of molecular democracy: Part 2

‘We used to dream big, now we have a district commissioner who does that for us.’

Last week I finished with the question: What happens when citizens, families and communities stop performing community functions as a consequence of being colonised by top-down institutional ways?

The answer, I believe, is: the collapse of community culture. It is said in psychological circles that a mother is never happier than her most unhappy child, if that is true it must also be true to say that a village is never happier than its most unhappy parent. A village without a community culture is a sick place. I can never be well in a sick village. So at the root of many of our social maladies is the ‘village problem’. The remedy for which is (largely though not exclusively) collective civic action in a citizen-centred democracy, the application of civic muscle in the stewardship of abundant communities.

However, in the same way that a muscle atrophies from lack of use, so too, do the health, wealth, and wisdom producing capacities of a community, when their collective influence is not brought to bear on the 13 irreplaceable functions of community and civic life mentioned in Part 1 of this blog series. At its extreme muscle atrophy can bring about heart failure. In the same way cultural atrophy can bring about a sort of social ‘heart’ failure so to speak, the symptoms of which include economic, environmental and political malaise, enveloped within which, are the roots of gang crime, drug trafficking, failing schools, loneliness and a myriad of other health, socio-economic and political issues. Put more plainly, the root cause of most of our social problems if not all, is social fragmentation. For more info on this, click here.

These problems become further compounded when professional helpers mistake the symptoms for the cause, and use the existence of such symptoms to validate their interventions and the growth of their systems. With that in mind, isn’t it odd that every ‘institutional needs analysis’ concludes that what the ‘people who are being analysed’ need are the services of those who are analysing them?

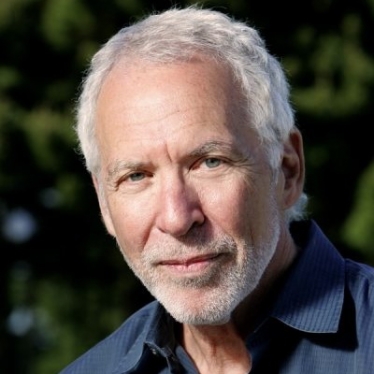

John McKnight

Hence John McKnight concludes: “The business of modern society is service. Social service in modern society is business.”

This helps explain why so many uncredentialed people believe that the only way things will get better for ‘them and theirs’ is if an outside expert comes in to make them so. No one is immune from the allure of this modern day bewitching. Not surprising given that our assets lay hidden behind such colonial ideologies as consumerism, managerialism and globalisation. Hence why so many of us find it so hard to believe that our economies, ecologies, and even our health and wellbeing, are (substantially though not sufficiently) within our sphere of influence.

We doubt our non-professionalised selves and our unaccredited neighbours, we doubt our potential power, and we shudder at the prospect that we might be the ‘cause’ of democracy, not the ‘effect’. Our service economies apply the ointment to that doubt, with the perversely reassuring professional words: ‘don’t worry, you’ll get better if you accept that we know better’. From fiscal banks to food banks we are clients, needy passive recipients. Our rights are defined exclusively by what we receive, with little mention of what we have a right to produce and co-produce. This clientalistic mindset is grounded in an ideology that views poor and labelled people as non-producing, and frames justice solely in terms of the service and programmatic idiom, in place of income, choice, control, and community.

Louis Althusser. Photo ©Vimeo

The scarcity ideology at the heart of the economic global system -that in turn drives our service economies- goes unnoticed for the most part, as do its consequences.

As Louis Althusser notes ‘ideology can perform its function only if it is not recognised as ideology, if it is recognised as the way things have to be’.

Yet there have been moments in history when the institutional world and it service/programmatic idiom has been constricted and consequently recoiled –if only for a moment in history-out of civic space-long enough to show just how sophisticated the ‘Demos’ can be.

Image taken from austral.edu.ar/

The Civil Rights Movement in the U.S at key stages throughout the 60s; the citizen response movements in Christchurch; New Zealand following the earthquake in 2011; the recent emergence of the Solidarity Movement in Greece. Indeed with regard to Greece after seven years of obscene austerity measures, last week’s referendum put it up to the Troika as never before, but also illustrated in undeniable terms the sophisticated capacity of citizens to engage in deliberative democracy.

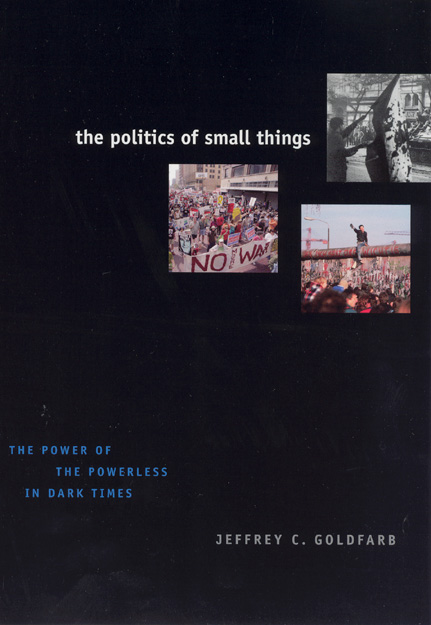

These are of course just some of many examples of the Politics of Small things at play[1]. Less well known, but no less important, are the countless imperceptible moments of civic action, and mutuality that see people step over such ideologies into self-determination. Moments like this in Bristol where Lucy Reeves, a Bristol resident, initiated Window Wanderland, a project that connected thousands of people across Bristol. You can visit their website here. Or the civic work that is under way in Hackney where local residents are intentionally acting as civic Doulas in the changing life of their street: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p02vyxqc

Or Damian Carter’s journey in getting to know 4,500 of his neighbours.

All of these belie the assumption that change happens with a big bang, and is swiftly signed into law across the Cabinet table. In truth as Jeffrey Goldfarb, author of ‘The Politics of Small Things’ notes, more often than not it happens in whispers, across a million kitchen tables, where people feel free to deliberate, disagree and still break bread together.

In a world that has become schooled in the value of professionalisation and massification, these are significant moments in time where people act as if they can be the primary shapers of their world, and prove themselves right in the act of doing so. These are moments when the prevailing map goes up in smoke and the territory starkly reveals the truth, or at least as valid a version of the truth as any other: if anything of enduring worth is to rise up from these ashes (and assets!), it will be as a result of our collective efforts at local level. That is precisely what is happening in Greece, and what happened previously in Poland, and hundred of other countries and jurisdictions around the world.

“Political change doesn’t always begin with a bang; it often starts with just a whisper. From the discussions around kitchen tables that led to the dismantling of the Soviet bloc to the more recent emergence of Internet initiatives like MoveOn.org and Redeem the Vote that are revolutionizing the American political landscape, consequential political life develops in small spaces where dialogue generates political power.”

Jeffery C. Goldfarb.

Franz Kafka ©Wikipedia

Franz Kafka, the Czech writer and public intellectual, cautions that “every revolution evaporates and leaves behind only the slime of a new bureaucracy”. Our industrial systems, even those that emerge following a popular revolt, for the most part assume that socio-economic problems and societal breakdown in families, and communities -especially in low income neighbourhoods- are the net result of a deficiency of one kind or another within such people and their ‘sub-culture’. Which in turn ‘proves’ the need for more technocratic services, either to police them or rescue them.

In actuality societal breakdown is not the result of deficiencies within the human condition. It is the result of the incessant attempts by elites to out maneovre (manage) the limits of our human and ecological reality, through unfettered corporate expansionism, managerialism, aggressive technological developments, and the commodification of human care. So that in turn we can engage in unlimited growth and wealth creation and consume more stuff. The price is personal and collective dissatisfaction, loss of economic sovereignty, and the degradation of our ecologies and indigenous cultures. When people lose the sense of their indigenous capacity (13 functions of people powered change) they become cannon fodder for the market place, and consequently, what was once done by communities is outsourced to the service-land.

Peter Block ©Craigslist Foundation

John McKnight and Peter Block conclude that this outsourcing of ‘care functions’ for our children and our neighbours’ children, has led to the significant “loss of basic functions belonging to families and neighbourhoods. Most have become incompetent in terms of doing the work of families and neighbourhoods. The cost of this incompetence is families and neighbourhoods that have no real function.

“No group persists when it has no reason to be together. Therefore, if families perform no functions we can predict that they will fall apart. We delude ourselves if we think our high divorce rates are caused by interpersonal problems and disagreements. It’s not that people are not getting along; it is that they don’t need each other because they have no functions to perform. They are just isolated, unproductive, dependent consumers who happen to live in the same house.”

Contrary to what we may have been schooled to believe, rediscovering our basic familial and civic functions is therefore more pressing than addressing our basic needs, since ironically performing our basic civic functions provides us with the purpose through which we can find the resilience to address our basic needs. And where our assets are insufficient to the task of addressing our basic needs, we can ensure that when we leverage in outside assistance we do not pay for it with our social capital, indigenous culture, and productive capacities.

I fully appreciate that the implication of all of the above runs contrary to the general view that things improve when our institutional systems and their leaders get their act together. Nevertheless, I fully believe that if we are waiting for our systems to reform and our leaders to redeem themselves before we act, nothing will change. We are our best hope for the future, but only if we can learn to act powerfully together and become producers of the future.

©Hannah Arendt Cente

The brilliant social and political thinker Hannah Arendt in exploring the relationship between power and violence, contrary to Mao Zedong, believed that power does not come ‘out of a barrel of a gun’ (Arendt 1972, 113). For her, power and violence are distinct, indeed violence irrupts in the absence of real power. Power for Arendt emerges as consequence of communities of consenting citizens acting in concert: power is consent in concert. In modern lingo we might say that what she was describing were non-hierarchical networks, flat organic systems, operating to the rules of the commons, hence functioning as social movements. In any case they stand in contrast to institutional structures that are for the most part encased within a hierarchical exoskeleton, where the few control the many in the name of standardized production of goods and services.

Our systems are not designed to produce health, wellbeing, safety, prosperity and so on, certainly not unilaterally, and certainly not to produce the quotients that communities are best placed to provide. Put simply, in every indigenous community there are irreplaceable health, safety and prosperity producing capacities that are at least as, if not more, sophisticated than any institutional proxy. Think breast milk versus formula milk; think functioning 12 Steps AA groups versus pharmacological interventions; think toast masters versus professional coaching in public speaking.

Here’s the rub, the institutional world has a switch which can go from ‘advance’ to ‘retreat’. Most institutions whether for profit, not for profit, government or non-governmental, are stuck in the ‘advance’ mode. Hence when they see a supposed need, they don’t ask ‘can this be addressed at local level?’, and ‘how might we support such a process?’ They simply advance to address the need. Then further compound the situation because their advance mode is not seeking to advance viable solutions to the problem they are addressing, but rather to advance their own growth and progress.

Hence, most institutions sustain the very problems they believe they are solving.

However, the overall solution is not to flip the switch to ‘retreat’ mode, as that would just trigger a whole set of other moral dilemmas, the odious neo-liberal agenda chief amongst them. But to figure how the system can loosen up and switch between modes to allow for proportionate responses to given situations. The only way this can work is if citizens have the power to govern in a participatory and not just a representative sense, in other words, as argued previously if we create a citizen centred democracy.

There will be times when in a citizen-centred democracy the demos will want big government, be that to face down Monsanto (choose any location you wish), the Troika in Greece, or the Banks in Iceland. And there will be times when we want Government to be more facilitative, to lead by stepping back. And so a citizen-centred democracy cannot therefore be built on Big Society, or Big Government, any more than it can be built on small society, or small government, it must be built on proportionality: in right relationship to the given situation, and that can only happen when it is citizen-led. Next week’s blog explores in some detail what that might look like on the ground and what is the optimum scale of such an civic endeavour and also discusses the cult of scarcity.

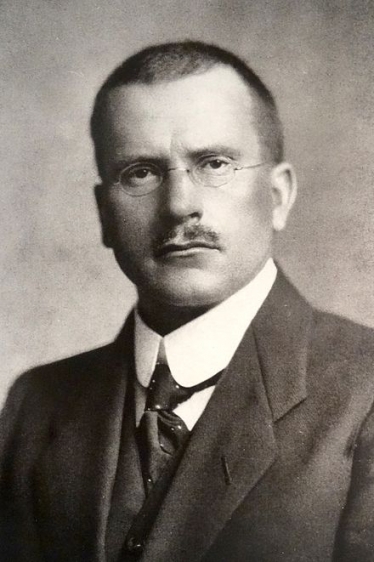

Carl Jung ©Wikipedia

All of this reminds me of a story I heard about Carl Jung, the Neo-Freudian Psycho-analyst, when I was in South Africa in 2009. I’ve subsequently tried to find a reference but have failed, so I can’t attest to its veracity. So, Anyway… as John Cleese might say: As the story went, Carl Jung while travelling in South Africa met a Zulu Elder. Not surprisingly Jung engaged in a discussion about dreams and was very pleased to find the Elder very engaged. Jung remarked that in his experience there are two categories of dreams typically. The more banal ones are concerned with day-to-day living; and then there are those that relate to visions, dreams of the future, of higher meaning and so forth. Jung chanced to say that he thought perhaps people in the West are more caught up with the first, and that perhaps people of Africa were more inclined towards the later sort of dreaming.

To his surprise the Zulu elder said: Yes I have those kinds of banal dreams regularly, just as you do, and yes, we once also had great dreams of meaning and purpose, dreams where we were the producers of our own future. But now, sadly, the district commissioner has them for us.

See you next week.

Cormac Russell

[1] The Politics of Small Things THE POWER OF THE POWERLESS IN DARK TIME

Soni Cox, My Way Code CIC

Just by you naming this fills me with hope and excitement. My own project is to bring a opportunity to shine lights on areas of people’s lives so they make the choices. They are the experts, they choose their path. It trusts people to tune into what they already know inside (away from the nanny state) and seeks to celebrate the emergence of their autonomy. So trying to ‘pitch’ this? Trying to build a ‘business’ with the same model (not swallowed up by the outcomes measured by public funding) and functioning as a team without the ‘slime of bureaucracy’ is an even larger challenge.

Thank you for writing this.

Soni

My Way Code CIC

@MWCSoni

nurturedevelopment

Many thanks, Soni,

We appreciate you take the time to write this. Also, hugely appreciative of your creative acts of community building. Keep on keeping on!

Cormac

jangriffin1

Brilliant!!!! , I have worked within social care for many years and felt the frustration of being told to turn of now its pm or they don’t fit our criteria even having to refer on to other organisations after working in partnership and creating an action plan that a person is happy and motivated to run with, with minimum contact they are then sent around all other services to tell their stories over and over again and sometimes right back to me looking and feeling totally confused, even more frustrated when possibly a year later we start their plan

I am out of this rat race now and loving the freedom to care, people are not soft they just need what they need at they time not being made dependant to keep big egos in work for ever