Communities and the State: a question of proportionality

First, let me say thanks to everyone who took time to participate in the conversation around last week’s blog. Building on that conversation, I’d like to start this post with a ‘hat tip’ to George Monbiot’s article: Neoliberalism is creating loneliness. That’s what’s wrenching society apart (12 October 2016) in the Guardian, in which he asks, “What greater indictment of a system could there be than an epidemic of mental illness?”

Most strikingly from my perspective, he concludes with a reflection on what we must do as a society to respond to this epidemic, by saying: “This does not require a policy response. It requires something much bigger: the reappraisal of an entire worldview. Of all the fantasies human beings entertain, the idea that we can go it alone is the most absurd and perhaps the most dangerous. We stand together or we fall apart.”

I would add, and emphasis another and equally absurd fantasy, namely that institutions -which are systemically oriented towards treating people as individual clients of their services- are in any position to unilaterally resolve loneliness or the root causes of any other socio-political issue.

The primary implication of Monbiot’s argument is that the fantasy ‘that we can go it alone’, is bolstered up by the belief that we don’t really need each other because our ‘good life’ can be found in the marketplace. He notes that the price for holding such a belief is our very wellbeing, and in particular our mental health. While he acknowledges that formal institutional programmes and wider legislation have a part to play in addressing this modern malaise, those contributions must be proportionate to the role of communities.

Like it or not, Public Sector and Third Sector programmes are the human services side of that very same marketplace, which has made us sick. When you peel back the narrative that describes their values and their vision and why they ‘care’, what you find is the same hierarchical exoskeleton as a commercial business, with the same dilemmas and limitations. Hence why Professor John McKnight takes great care throughout his book, Careless Society, Community and its Counterfeits, to point out that regardless of how caring public servants and not for profit employees are, that the institutional systems they work for don’t care. He does not say this to run systems down, in fact he is saying it so that we can stop burning the people in our systems out, by asking them to do our caring for us.

Hence if we are to disambiguate public services and NGO programmes in any real way from privatised goods and services, then we must ensure that what they offer goes beyond current services provision, which too often defines us out of our community networks, and into services as clients. The alternative future for charities and third sector institutions therefore, must surely involve standing more in solidarity with local citizens as they work to reweave the social fabric of their communities, and advocate for greater income equality, as well as providing services.

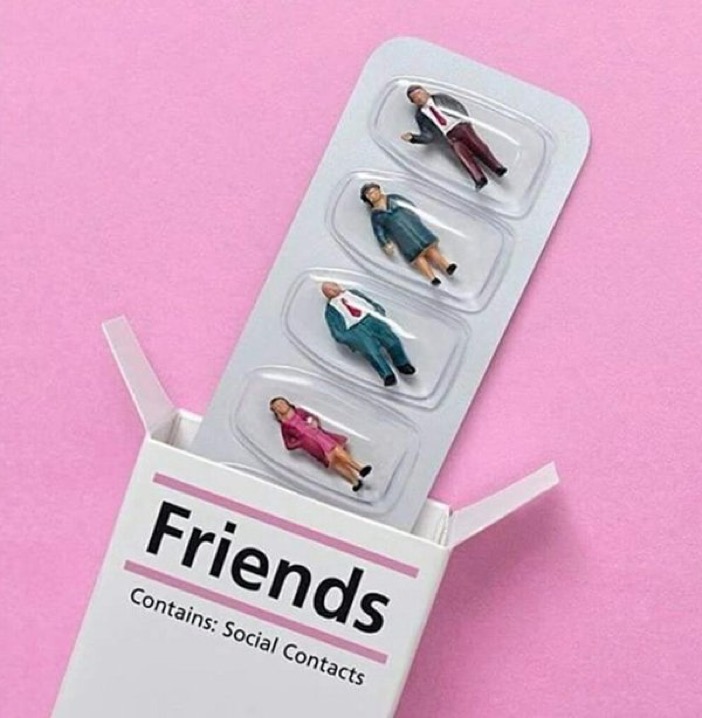

Put plainly, the bottom line is that there simply is no institutional service, programme or technology for ending loneliness since it is not a service issue. It’s a civic one, and therefore requires what Ivan Illich called Tools for Conviviality: we best counter loneliness by building community.

Essential but not Sufficient

Margret Wheatley goes further to claim ‘whatever the problem, community is the answer’. But is that a step too far? Is it not more accurate to say, ‘whatever the problem, community is an essential but not sufficient part of the answer?’ Or as Prof. Jody Kretzmann, Co-founder of the Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD) Institute regularly says, ‘ABCD is essential, but it is not sufficient’. I think it is very important that we make this amendment, especially in the current climate where some institutions are now turning to communities to ‘step up’, and fill the space of services that are being cut.

The reality is that there are limits to local capacity (to what communities can do alone), as are there to what institutional systems can do unilaterally. There are certain things that communities do best themselves with no help from outside, while other endeavours are accomplished best mainly by communities albeit with some outside help from agencies, and yet other challenges demand outside agencies do things for citizens and their communities.

Mindful of this, the Kettering Foundation, who have spent decades studying what happens when democracies function as they should, suggests that the democratic conversation we need to have should centre on understanding what are the irreplaceable functions of community, and only then to move on to reflecting on the functions of an enabling state, and how those unique and irreplaceable functions can become mutually reinforcing of the democratic experiment. This is classic Asset-Based Community Development applied to the wider political landscape.

To have that democratic conversation we need to be honest about the issue of power, and further recognise that communities can’t know what external resources they need, until they first know what internal resources they have and how to join them up productively and inclusively.

Institutions are not benign -regardless of how well intentioned their staff and boards may be- when it comes to power relations between communities and organisations. Therefore, if we start the conversation with, ‘what can institutions do for you, or {even} with you?’ we will undoubtedly end up where we began, with marketised, individualised, professionalised answers to social and political issues. This is why the classic model for assessing needs is no longer fit for purpose.

Has it ever struck you as odd that every needs analysis draws essentially the same conclusion: that what those who are being analysed need are the services of those who are analysing them? Time and again, people’s actual needs are confused with an agency’s categorical imperatives, and so the ready-made remedy comes to define the problem not as it is, but in terms of how it fits within the system.

The good news is that there is a way around this. We could intentionally re-sequence the questions, breaking with current custom and practice and starting with what it is that citizens and communities can contribute to their own wellbeing, then working out from there to what agencies can contribute. I believe that this sequence will enable far greater participation and radical inclusivity and so result in more equitable, pluralistic and communitarian outcomes. We will over time also achieve what George Monbiot proposes: “the reappraisal of an entire worldview”. But to get there we need to work at a scale where people and their associations can get in on the action, not as clients, or volunteers, but as citizens in their own right. And to achieve that, we need at least to start seeing the neighbourhood as a primary unit of change. {Important to point out here, I am not suggesting we do that at the expense of minority groups who all too often are excluded from communities of place}.

At neighbourhood scale we can have a citizen-centred rather a consumer centric conversation that over time and, at the speed of trust, asks the following questions in relation to resident/citizen concerns:

- What are the things that only residents/citizens can do in response to this issue?

- What are the things that residents/citizens can lead on and achieve with the support of institutions (governmental, nongovernmental, for profit) in response to this issue?

- What are the things that only institutions can do for us?

- What are the things that institutions can stop doing which would create space for resident action?

- What can institutions start offering beyond the services that they currently offer to support resident/citizen action?

These questions and their sequence make good democratic sense in a world where governmental institutions and not for profit organisations are understood to be an extension of us, rather than a replacement for us.

But, now let’s imagine for a moment a world where programmes and services are widely thought of as the best of all available options in the production of welfare. A world where local residents and citizens in general are thought of, and think of themselves, solely as consumers with rights to receive those services, but with no (right of production) capacity to contribute to their own wellbeing and the wellbeing of their families and communities.

In these extreme circumstances it’s possible to imagine how some might consider these questions as neoliberal, particularly in a time of austerity. And that’s what’s happening in some quarters, see last week’s blog for a case in point. Friedili offers an excellent critique of this here , where in short she notes that there is an increasing trend towards institutions busily recruiting volunteers to pepper on the social problems they once paid practitioners to address. She rightly criticises a growing trend, which sees agencies that purport to be using Asset-Based approaches rationalising their cuts on essential services and programmes on the basis that in these economically difficult times, communities must dig deep and do for themselves and each other what was previously done to or for them by the state and its partners.

Accordingly asset-based approaches which have jettisoned community development have become the darling of public health, the public sector and big funders like Big Lottery in the UK, but all too often have become a shadowy version of ABCD. Asset-Based approaches offer no real distinctions between personal development, classic top-down relief and effective citizen-led community development (see Wendy Craig blog). Hence when you say the words Asset-Based Approaches, people are as likely to think about Mindfulness techniques as they are to think about community building. In truth they are more likely to think of the former than the latter. It is a travesty for which no one person or organisation can be blamed, but by which everyone is tarnished.

Bizarrely the very language that spelled out associational power and citizen action has come to mean ‘Lego workshops’ and signposting people to yoga classes. It is for this reason that I have been actively distancing our Asset-Based Community Development practice in the UK from Asset-Based Approaches. You can’t have true Asset-Based practice without Community Development, and you can’t have sustainable Community Development without Asset-Based practice. When you decouple the CD from the AB, you end up with a watered down, rudderless version of the approach, and all of the critiques presented by Friedli become absolutely legitimate. Equally though, when you decouple the AB from the CD you end up with a version of Community Development that no longer concerns itself with neighbourhood community building, instead favouring targeted group work and advocacy for policy reform and service redesign. Surely both are needed, and sequencing matters.

And so in conclusion, we are back to the running theme of this post: right relations between the functions of community and institutions. Noting that when separated from each other these functions are ‘essential but not sufficient’. In a time of fiscal retrenchment and an age of deepening neoliberalism and consumerism, if we are to avoid some institutions overwhelming communities with their newfound ‘do it for yourself philosophy’, we need take a number of very practical steps.

- We need to state clearly that ABCD is not an alternative to services, nor is it an alternative way of providing services.

- We need to offer practical facilitative supports that enable communities to reconnect, with no strings attached. In other words we must be willing to accept that the objective of community building is building community, not better service outcomes. It has nothing to do with services.

- We need to be clear that there is a significant difference between Asset-Based Community Development and Asset-Based Approaches.

- We need to state clearly that the communities we are speaking about are the ones that are struggling to build the commons outside institutions in what the German philosopher Husserl called the Life-world, and what Illich referred to as the vernacular realm. What we more simply think of as associational life.

- We need to state clearly that a good life is not determined by how dependant one can be on services/programmes (though dependable services matter in the right proportionality to our social networks) but by how interdependent one can be in community life.

- We need to be clear that ABCD is not about saving institutions money, but about saving people from a life of institutionalisation, which is no life at all.

There are limits to everything, and it is within those limits our unique gifts flourish and new relationships are sought out, and blossom. Or as Leonard Cohen so beautifully puts it:

‘There is a crack in everything. That’s where the light gets in”.

Cormac Russell

Wendy McCaig

My top 3:

1. ABCD is not about service delivery.

2. ABCD is about building community.

3. Having a few token citizens serve on your team does not make it ABCD.

So in summary Asset Based Community Development is about COMMUNITY BUILDING simply for the sake of building a community.

I feel your pain. We are having the same confusion in the USA with people trying to pretend that all “Asset Based Approaches” are ABCD. In our proposals we are using CDCD – Citizen-Driven Community Defined initiatives to describe what a healthy ABCD effort looks like.

Seems like we spend more time talking about what ABCD is NOT than what it is.

Thanks for another great post and for helping me not feel so all alone in trying to keep the model pure.

My greatest challenge is not “individual betterment” approaches verses “Community development” approaches. It is more institutions with a few “citizens” serving on their team but serving the institutional agenda with no real power to create their own responses. They basically link institutional programs to the neighbors by recruiting neighbors to be their spokesperson and call that ABCD. It is so frustrating that there are so many shadows of ABCD and so few authentic pure models to point to.

Emily Messieh

Wendy – I love what you have said here. I am finding the same challenge here in Australia. If you find answers or better ways of doing this, please let me know. I’d love to chat more.

Cormac Russell

Thanks Wendy, what you say and how you say it resonates, thanks for building on this important conversation. BW Cormac

David Week

Monbiot! Not Monibot. 🙂

Shaun Burnett

Great spot David. Changed now, Shaun

Emily Messieh

YESSSSSS! Cormac YES! I love what you are saying here and leading this discussion with. Wendy McCaig – I love what you said also. Let’s keep this conversation going. Let’s get the roots down and speak honestly about this. And let’s mobilize citizens and our communities to go the direction they want to – not the direction we want them to.

James

We’re having the same conversations here at FM. Also shaping our thinking around the next ABCD England get together and continuing this conversation

Caitlyn Mccarthy

Hello, I have just been employed as a project manager to set up an ABCD project for a local Charity and would be most grateful if you could add me to any mailing lists you have to receive information about the next ABCD England event? I am also interested in visiting some Learning Sites in the UK to get a deeper understanding of ABCD and to get inspiration. Thanks

Shaun Burnett

Thanks for getting in touch, I’ve sent across an email. Speak soon. Shaun

Chris Chinnock

“You can’t have true Asset-Based practice without Community Development, and you can’t have sustainable Community Development without Asset-Based practice”. LOVE this statement!