No Experts in Matters of Judgement – Part 3 of 5

The hand of experts is evident in near every part of our modern lives, from the standards applied to the stuff in our medicine cabinets, to the food in our fridges. From the books that we read, to the quality of foam on the beds in which we sleep; the expert on regulation, industry standards, quantity of this, and millimeters of that, has had their say. In fact, there are few things that we use or consume in our daily lives that have been weighed and measured that do not have the fingerprints of someone’s expert knowledge and regulatory oversight upon them. All to the good.

Most of us go about our daily lives, unknowingly benefiting in a myriad of ways from the efforts of this army of experts, that we the public never meet, yet whose decisions pervade every waking and sleeping moment of our lives. But does it work the other way around, are the voices of ordinary folk permeating into the professional lives of the regulators to the same pervasive extent? David Matthews in ‘Ecology of Democracy’ argues that they are not, that in fact the public voice is all but absent in our public institutional decision making processes, and that’s a big issue, not just in terms of ensuring that expert knowledge is used, but for democracy itself.

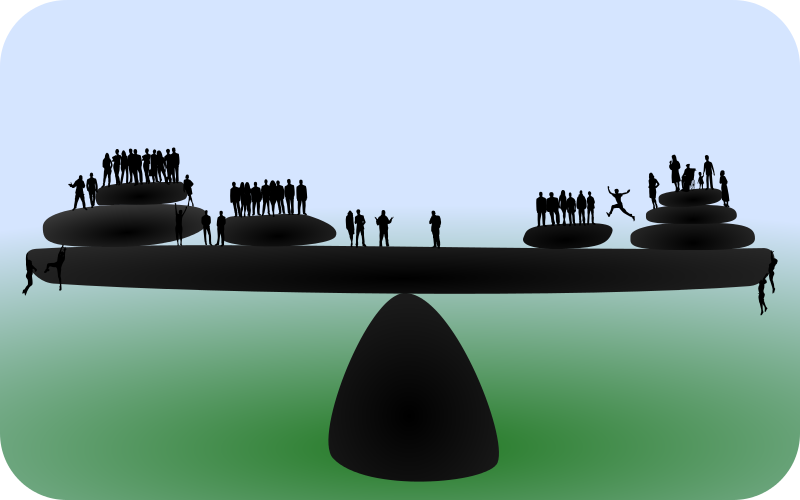

Matthews notes that public judgement is essential for good governance and decision making at state and local government level. That it is, in fact, public judgement that legitimizes government functions and the experts and public servants who work within them. Put most starkly, if a democratic government does not have public confidence and therefore is not seen to be legitimate in the eyes of the public, in the absence of civic cooperation, it will surely fall. Because in truth, in matters of wellbeing, justice, wisdom and safety, if citizens and communities withdrew their contributions in the morning, we would within days begin to see just how much the citizenry contribute to a flourishing society. Institutions do not have a monopoly on health production or education, when they function as if they have, the three domains of knowing fall out of kilter and we all suffer. History bears this out.

Recounting the Noble prize winning economist Eleanor Orstrom’s thesis, on the centrality of Co-production (co-production of Citizen to citizen action) to a functioning society, Matthews points out that public judgement works differently to how expert knowledge functions and of course it largely plays out in different arenas.

The challenge he posits is that there can be no experts in matters of public judgement, because essentially public judgement is produced through collective deliberation of the many – often equally legitimate – but competing options. Hence why judgement is required. Public judgement is the weighing up of matters that do not get resolved by the application of technical or factual know-how, and do not succumb to the orders or policies of someone’s assumed authority.

Is it about Chlorine levels or Safety?

Is it about Chlorine levels or Safety?

Everyday newspapers produce ‘water quality reports’. Having said that, you would need to be some class of an expert in science to follow them, and so most people don’t read them. Does that mean the public don’t care or are disinterested about water quality? No, not at all; but most likely they are not (for the most part) interested in the specific quantity of chlorine that should be placed in our drinking water. They are however interested in whether the water is safe; if they and their children are in danger should they consume it. And through well facilitated deliberation citizens can and will engage in shared judgement making about the necessary trade off to ensure safe water supply. Just think about the Flint Michigan scandal of last year in relation to their water supplies and it becomes clear how much the public do care about these issues. The question is how do we facilitate such conversations. Citizens Juries are one very good answer, but there are many others. Neighbourhood community building is foundational among them.

A big challenge to communication across the expert and personal domains of knowing relates to the current, record low levels of trust the public have in their Public Institutions. But that cuts both ways, there are also some very pernicious trust issues going on between institutional practitioners and the citizens they serve. One senior civil servant recently put it thus: ‘communities are like ‘chocolate fudge’ to me, mostly sweet, but with far too many nuts to be dealing with’.

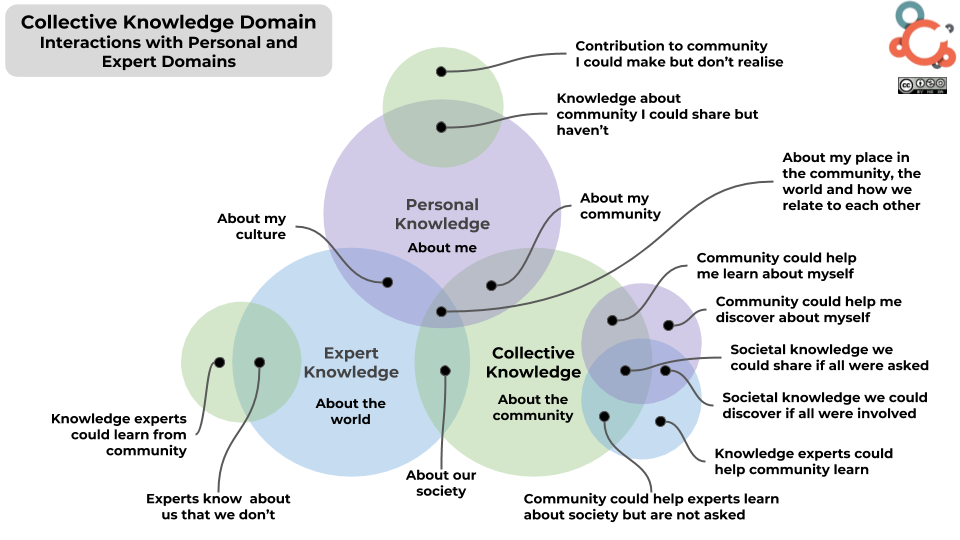

The solution is, I believe, less about improving the relationships between experts and individuals on a case by case basis (although that will help of course) and more about investing in collective knowledge and deliberation, which as previously argued will edify the other two domains and enhance communication across all three. The other solution relates directly to the domain of personal knowing and collective knowing, one of the unique capacities that individuals and civic associations have is the capacity to care, it is something we know how to do, that institutions do not. Accepting that institutions don’t care; that people do, is crucial to our understanding of where we should focus on making change happen. As John McKnight reminds us: “Care is the freely given gift of the heart from one to the other, you cannot manage it, buy it, sell it, or curricularise it.” How do we better liberate that capacity to care? Imagine if questions like these became the mainstay of public deliberation.

But there’s another question to consider here: what form might these deliberative conversations take if they became the norm. To answer this question, once again I turn to Peter Block for council. Here are the six conversations he recommends if we are interested in growing deliberative and restorative public judgement, in relation to matters that do not have a regulatory or factual answer.

The Six Conversations that Matter

- Invitation conversation. Transformation occurs through choice, not mandate. Invitation is the call to create an alternative future. What is the invitation we can make to support people to participate and own the relationships, tasks, and process that lead to success?

- Possibility conversation. This focuses on what we want our future to be as opposed to problem solving the past. It frees people to innovate, challenge the status quo, break new ground and create new futures that make a difference.

- Ownership conversation. This conversation focuses on whose organization or task is this? It asks: How have I contributed to creating current reality? Confusion, blame and waiting for someone else to change are a defense against ownership and personal power.

- Dissent conversation. This gives people the space to say no. If you can’t say no, your yes has no meaning. Give people a chance to express their doubts and reservations, as a way of clarifying their roles, needs and yearnings within the vision and mission. Genuine commitment begins with doubt, and no is an expression of people finding their space and role in the strategy.

- Commitment conversation. This conversation is about making promises to peers about your contribution to the success. It asks: What promise am I willing to make to this enterprise? And, what price am I willing to pay for success? It is a promise for the sake of a larger purpose, not for personal return.

- Gifts conversation. Rather than focus on deficiencies and weaknesses, we focus on the gifts and assets we bring and capitalize on those to make the best and highest contribution. Confront people with their core gifts that can make the difference and change lives.

Closing thought: citizens as producers

Often the challenge in supporting public deliberation on this or any other subject, is simply that our systems are not set up for it. Instead they operate at a two-dimensional level, where the focus is on the public as consumers (the ones with problems to be fixed) and our systems as producer (the ones with solutions for consumption).

I have wrote in a previous blog about the study by Nora Groce of the lives of the hearing impaired in Martha’s Vineyard; a study which discovered radically different outcomes in the quality of lives. These emerged within a spoken and signed language bilingual community, that eliminated the disability of deafness and instead created an enabled inclusive community.

Therefore, the most essential paradigm shift comes when we all start recognizing that citizens in a democracy don’t just pay taxes to consume services and ensure that those who don’t have resources are also cared for, they also personally and collectively produce health, justice, wisdom, and safety that is irreplaceable and of immense value (albeit largely invisible and or taken for granted). This is what Eleanor Orstrom means by co-production, where citizens join with each other and using their assets, produce health, safety, learning and prosperity. The state then becomes an extension of that production capacity, not a replacement for it.

Seeing the world in this way allows us to value all three domains. In this new way of viewing the world the Doctor for example (as illustrated by Dr. Atul Gwande in his book Being Mortal) will shift from questions in relation to end of life care, such as: “do we fight or do we give up?” To “what is the fight?” Taking a leaf from the Palliative care practice book, so to speak, they need to be asking the people they serve: “what does a good day look like?”, then figuring out how they can tap into their expert knowledge as doctors and surgeons to create a treatment plan that enables wellbeing as well as mitigating ill health. Hence using their expert knowledge to erect a dome of protection around the person’s vision of a good day and helping them to have as many of those days as possible.

It’s a brave new world, but a better one, not alone for the public, but also for the experts that serve them. Democracy works, when it works like this.

Next week I will look at the importance of framing the relationships between the three domains of knowing within a democratic context and exploring the practical means of enabling better proportionality between these domains. See you next week.

Next week I will look at the importance of framing the relationships between the three domains of knowing within a democratic context and exploring the practical means of enabling better proportionality between these domains. See you next week.

Cormac Russell

Part 1: Three Domains of Knowing

Part 2: The Shift from Expert to Collaborator

About the diagram: Knowledge Graph Key, Euler Diagrams.